Spatial analysts thought they could unite geography around a few spatial features. Their failure should not obscure the enthusiasm that reigned in the discipline some 60 years ago.

The trilogy of spatial analysis

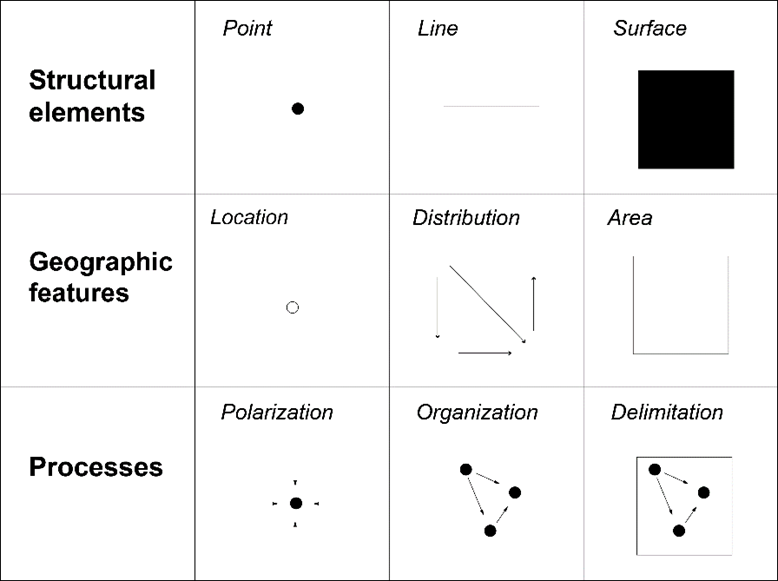

Geographers have long argued that space could be represented on a map by a combination of three fundamental features: points, lines, and areas.

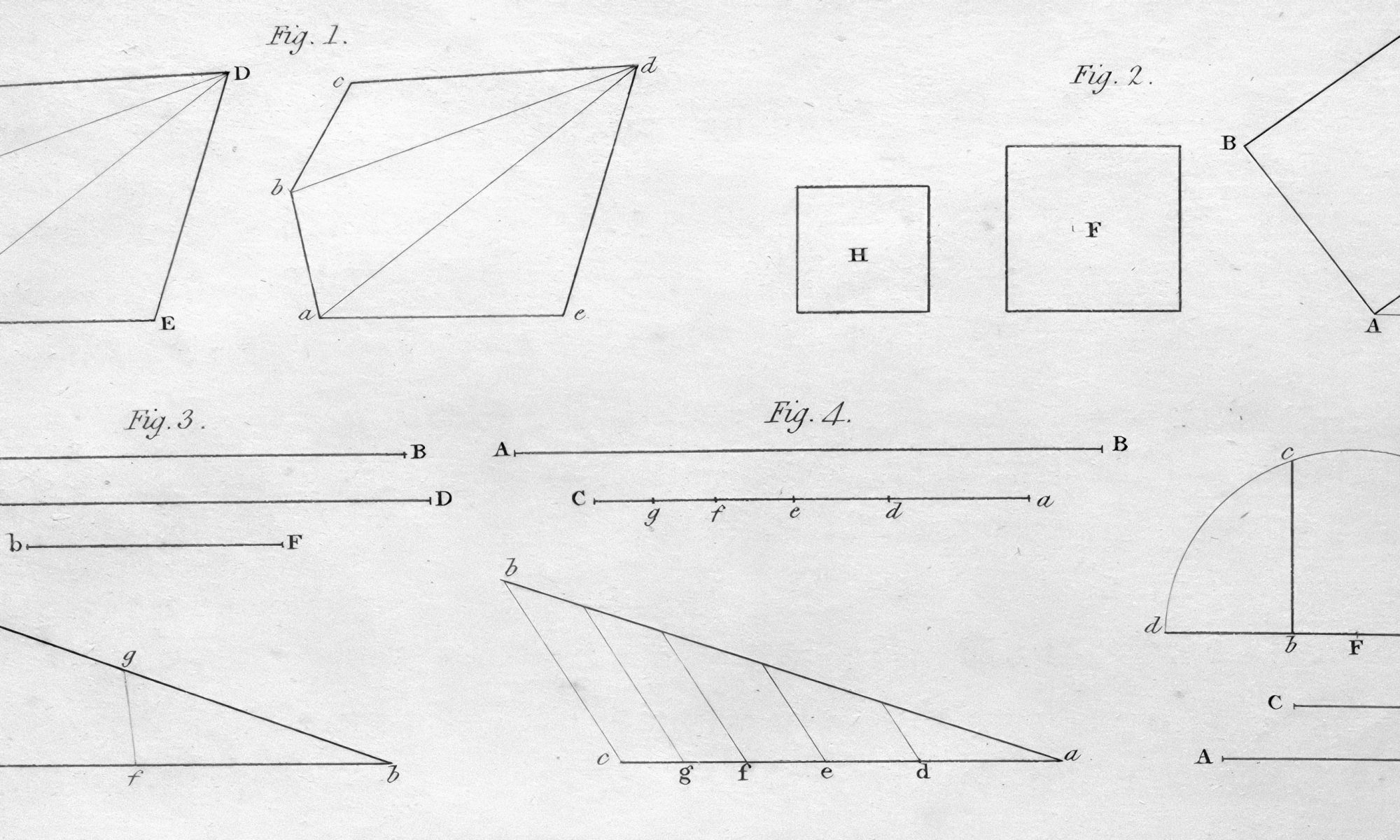

This trilogy, inspired by Euclidean geometry, is one of the foundations of spatial analysis, a quantitative revolution that contributed to making geography more scientific in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Points such as cities and markets play a crucial role in polarizing space by concentrating flows in specific locations. Lines such as roads and pipelines organize space, by distributing movements between places. Areas represent surfaces that have been delineated, such as the state.

Points, lines and areas

A more unified discipline?

The point-line-area trilogy has not only been used by geographers to make better maps. Some of them have argued that it could also contribute to get rid of the enduring distinction between human and physical geography.

In Theoretical Geography, published in 1962, Bill Bunge notes that “certain spatial solutions cut across traditional geographic subject matter areas”. For Bunge, the formalization of new organizational principles is an opportunity to rethink the old divide between the two geographies.

“As a matter of efficiency”, he proposes that geography should “start dividing itself into various theoretical spatial fields, such as point problems, area problems, description of mathematical surfaces”.

How to avoid disciplinary fragmentation

The idea is welcomed with excitement by Peter Haggett and Richard Chorley, who note in the introduction of their Integrated Models in Geography published in 1967 that Bunge’s idea “can be rigorously extended (…) to include complex combinations of the basic topological forms”.

Geometrical analysis, they argue, offers a “logical, consistent and geographically more relevant alternative to the ‘element-orientated’ approach” in geography, which inevitably leads to sub-divide the discipline into several branches.

As human and physical geography become more distant from each other, Haggett and Chorley note that they also come under the influence of other, more structured disciplines such as economics or meteorology.

The result is a continuous process of disciplinary fragmentation, which Haggett and Chorley explicitly tried to prevent in their own work. Their Network Analysis in Geography, published in 1969, models the structure of both transport and river networks to emphasize the complementarities between human and physical geography.

The spirit of a revolution

More than 60 years later, it is easy to argue that a reunification of geography under the auspices of spatial analysis was illusory.

We now know that human and physical geography have not come together. On the contrary, the two sub-disciplines have drifted apart, and no one really knows if they will ever come together again.

However, even if spatial analysts never succeeded in uniting geography, one can only admire the enthusiasm with which the new methods and concepts of the New Geography were embraced.

The ambition and boldness of their authors for a rethinking of geography should be celebrated. As Ian Burton wrote in the early 1960s, “When you are involved in a revolution, it is difficult not to be a little cocky”.

By Olivier Walther, 4/29/2025.