The number of violent events recorded in the last decade in West Africa is either independent of agricultural seasonality or increases with the abundance of resources.

The lack of seasonality in West African conflicts suggests that political violence does not have a direct link with environmental factors. Instead, the story of hunger is one of political power.

Measuring violence and food availability

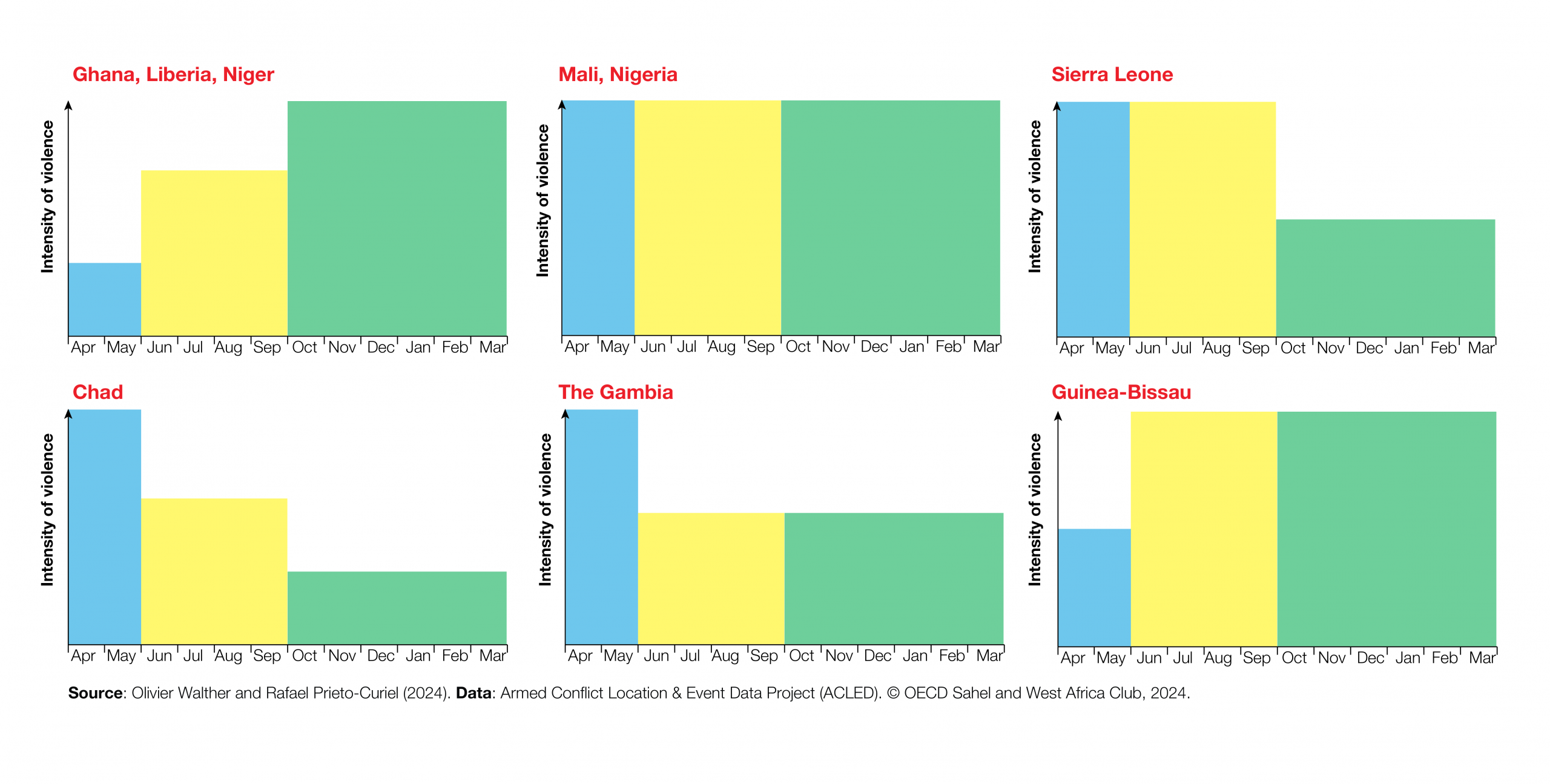

To measure the extent to which violence varies according to food availability, we divided the year into three main periods corresponding to those of the Harmonized Framework, which measures acute food and malnutrition in West Africa.

The pre-lean season starts in April and usually ends in May. It is followed by a lean season, called soudure in Francophone Africa, which lasts from June to September. The post-harvest period starts in October and ends in March.

Food availability is at its highest after the harvests, begins to decline during the pre-lean season, and is at its lowest during the lean season, as described below.

We then calculated how much political violence West African countries experienced during each season using disaggregated data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project from 2014 to 2024.

As in most of our previous studies, three types of violence were considered: battles, violence against civilians, and remote violence and explosions.

We designed three scenarios to study the seasonality of political violence:

- Violence may correspond perfectly with food availability, with a peak during the post-harvest period and a minimum during the lean season.

- Violence can also follow an inverse trend to food availability, with a peak during the lean season and a minimum during the harvest season.

- The two phenomena may also have no apparent relationship. In other words, political violence may obey different temporal rhythms to those of the seasons.

The results were presented at the Food and Prevention Network meeting (RPCA) in April 2024, along with another study on the geography of food and political insecurity.

Violence and food availability have their own life cycles

In Benin, Burkina, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, and Senegal, violent events decrease strongly during the lean season and increase during the harvests, as in our first scenario. This evolution suggests that conflicts may be fueled by the abundance of agricultural resources in these countries.

Only in Togo is violence higher during the lean season and lower during the harvest season as in our second scenario. This suggests that conflicts may be fueled by a lack of agricultural resources in this country.

In the other countries of the region, which include Chad, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Niger, Mali, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, political violence has not apparent relationship with food availability. As in our third scenario, violence and food availability have their own temporal cycles.

These results obtained at the country level are consistent with those of our previous analyses, which already showed that violence rarely corresponds to agricultural seasons.

From 2012 to 2019, for example, the highest number of fatalities related to the Boko Haram insurgency around Lake Chad is recorded in February, at the end of the post-harvest season.

A more detailed approach to the geography of conflict

Of course, our approach has limitations. From a geographical perspective, the national level may not be the best adapted to capture cycles of violence, as most conflicts tend to be fueled by local factors. This is particularly true in countries that experience several major conflicts, such as Nigeria.

Aggregating insurgencies that have their own life cycles contributes to blur the possible seasonality of violence. To better understand whether food insecurity varies according to conflict zones, further research is needed at the subnational level and on the different actors involved.

From a temporal perspective, dividing the year in three seasons is overly simplified. It is possible that a different breakdown between agricultural seasons could yield different results. Further research should therefore examine whether food insecurity varies according to the months that make up each season, or if even more refined time periods can be used.

To address these issues, we intend to build on a novel approach that we developed to detect trends and shocks in conflict intensity that would not necessarily be visible using standard time-series analysis.

A simplified version of this new tool is already available online. Different periods can be selected by region, country, and for a selection of violent groups operating in the Sahel. The ability to filter by type of violent event makes it possible to identify what kind of conflict is affecting a region and to study its possible seasonality, as shown below.

Recognizing the agency of conflict actors

The growing availability of data and technical tools makes it possible to examine conflict dynamics with unprecedented spatial and temporal precision.

For the potential of these data and tools to be realized, however, researchers must further explore the complex relationships between conflict and resources.

Assuming that political actors fight because of the lack (or abundance) of natural resources is simplistic. West African conflicts are not “hunger wars” motivated by a lack of agricultural resources and belligerents are not merely at the mercy of environmental factors.

As Tor Benjaminsen argues in his recent book, a political ecology approach recognizing the agency of actors and their historical and material context is more necessary than ever for understanding West African conflicts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marie Trémolières, Lacey Harris-Coble, Steve Radil, and Jose Luis Vivero. The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the OECD, CILSS or RPCA.

By Olivier Walther and Rafael Prieto-Curiel, 8/11/2025.