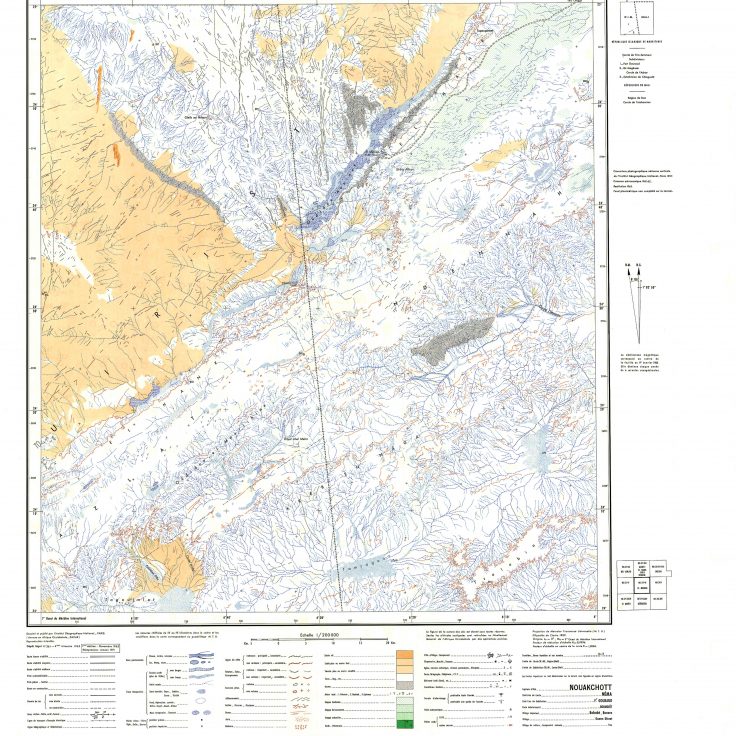

| 1- El Mzereb. In the far north of Mali, the Sahara is divided by a border line that runs for nearly 950 km towards the Niger River. This line in the sand is, however, of relatively recent origin. Until 1944, the colonial boundaries were located significantly further west and French Sudan included a large part of what is now eastern Mauritania, in the Néma region. |

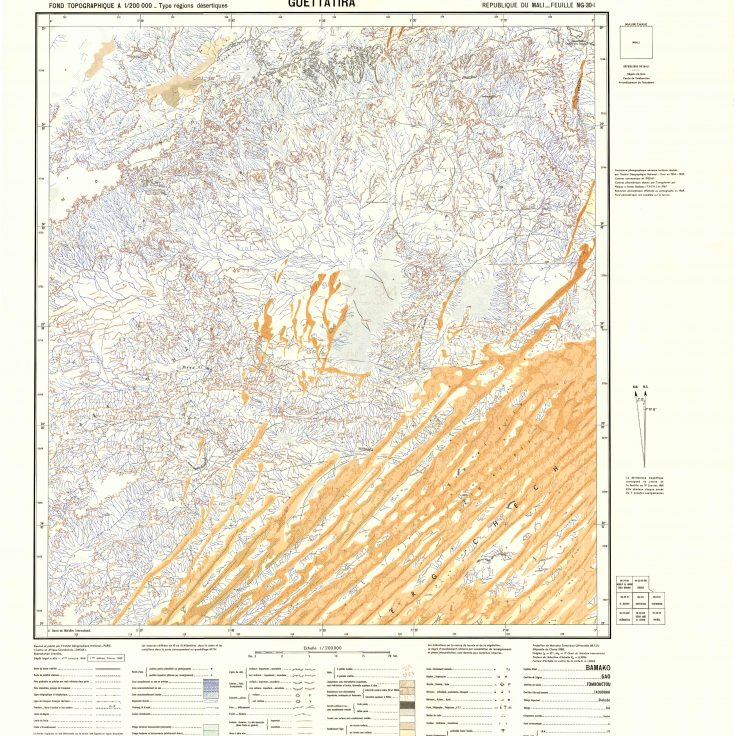

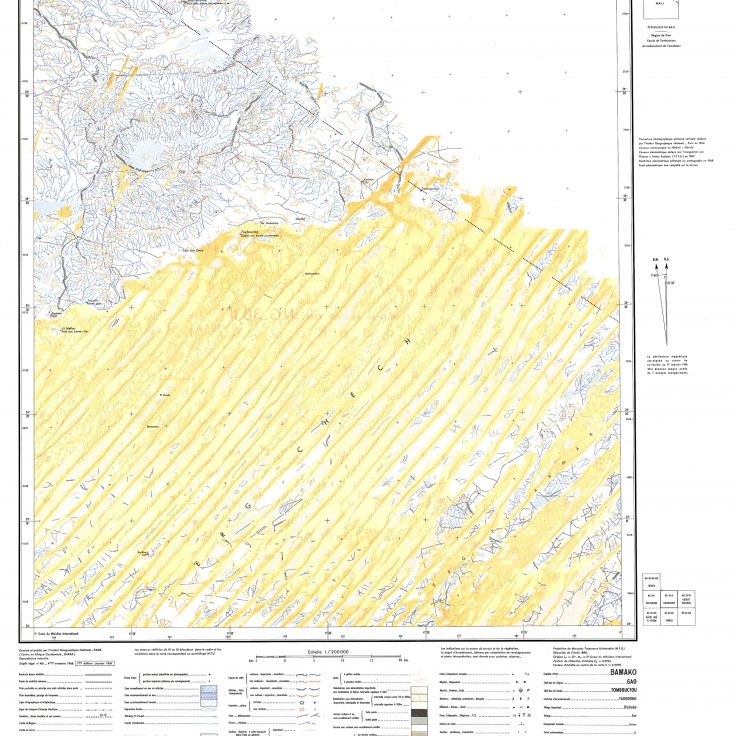

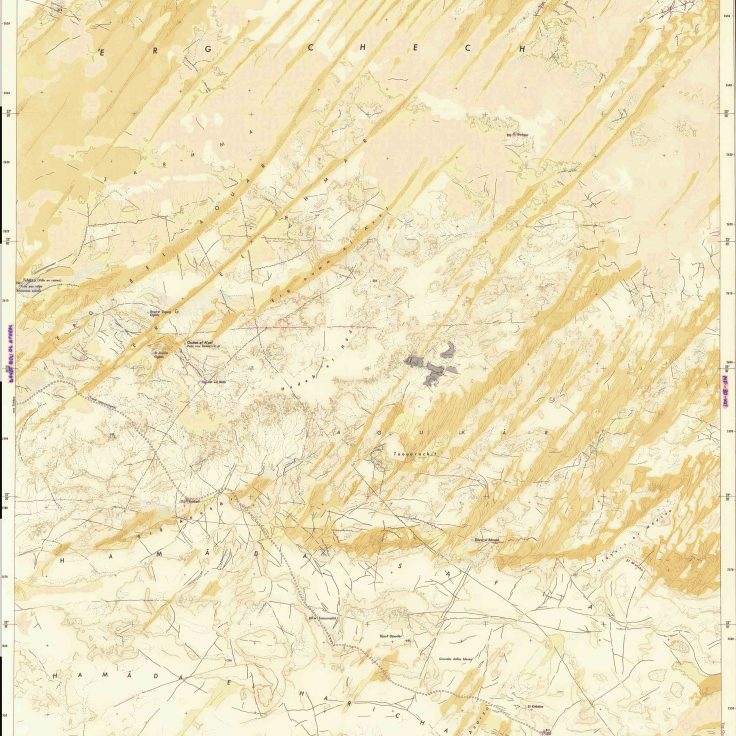

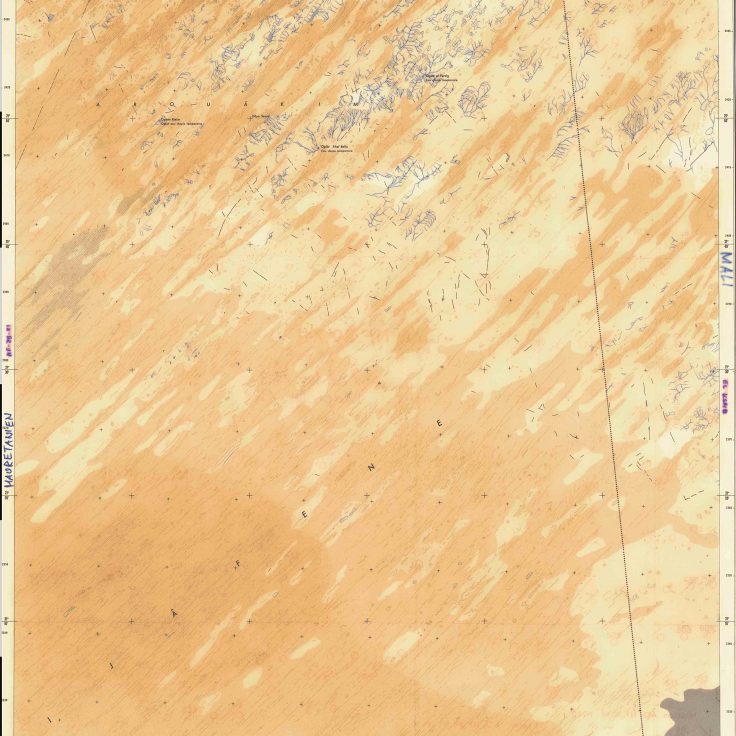

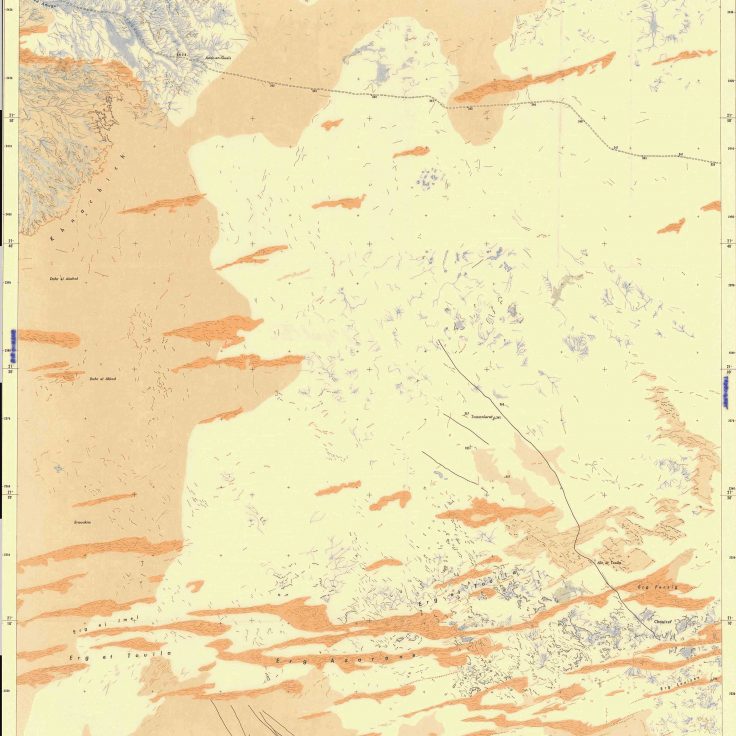

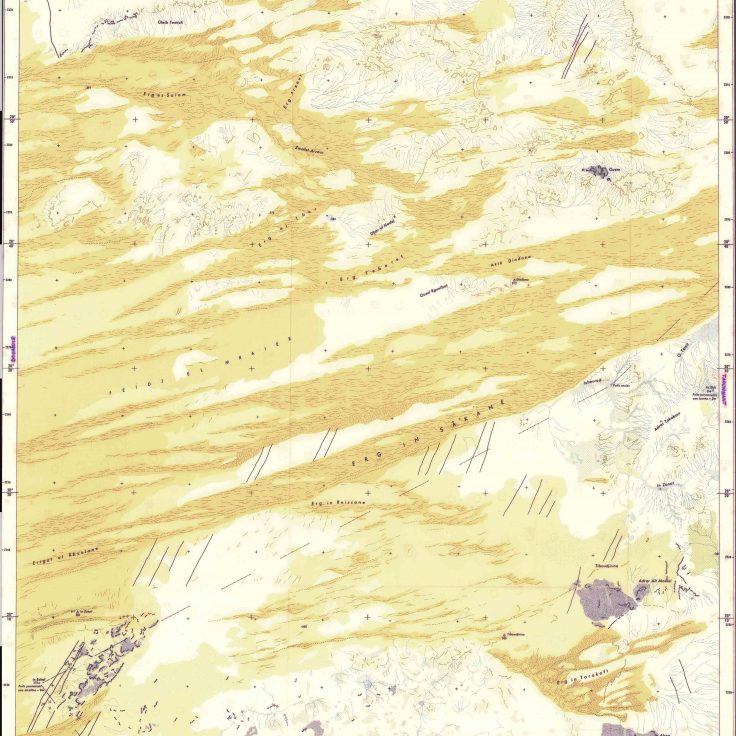

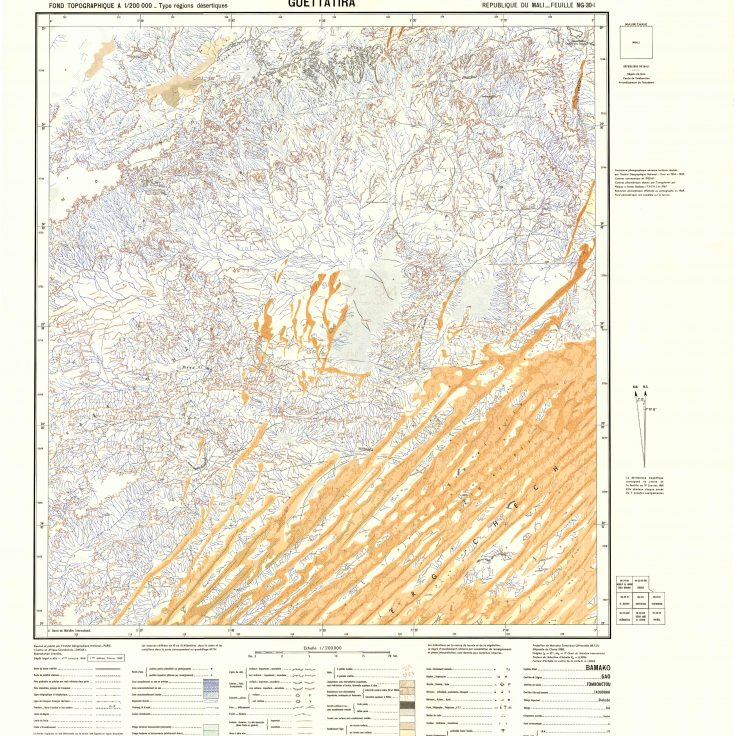

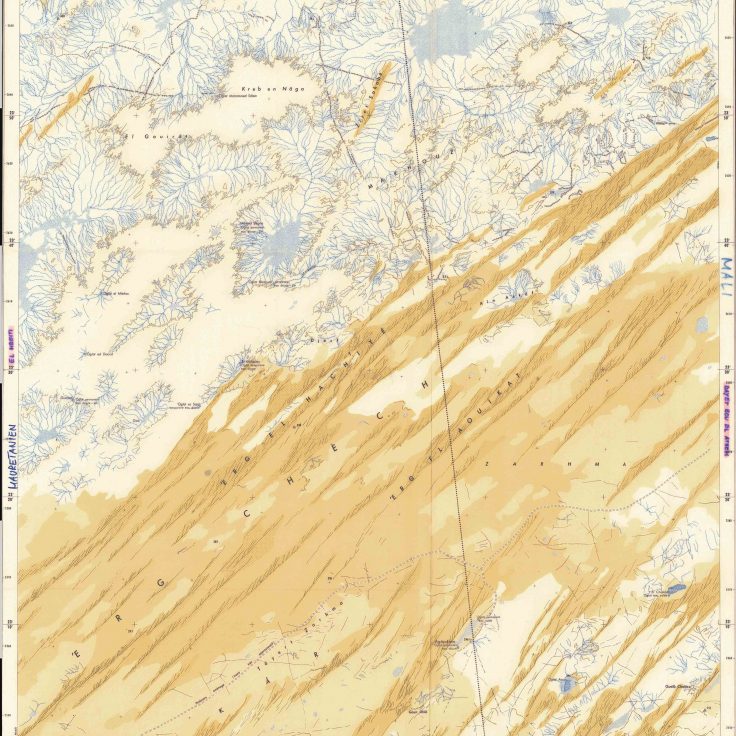

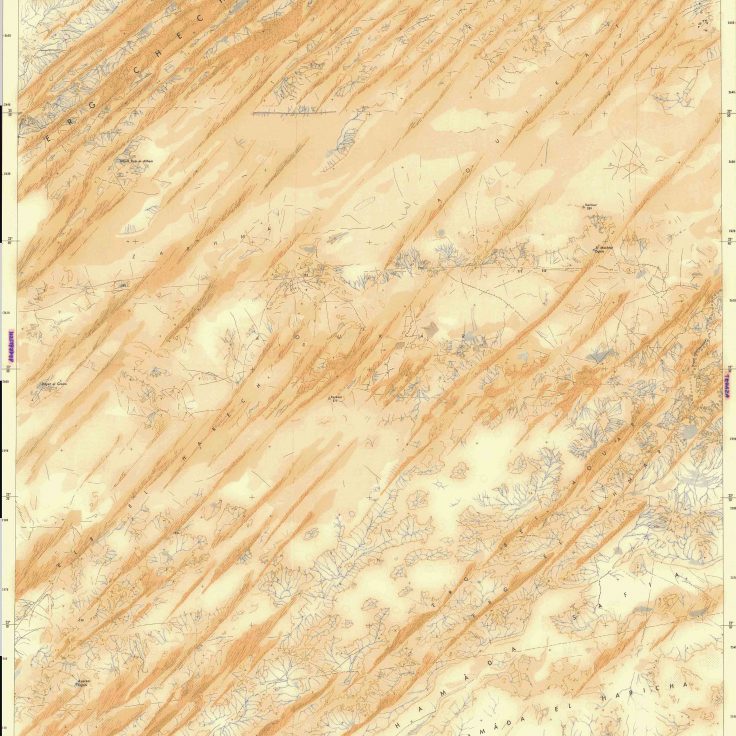

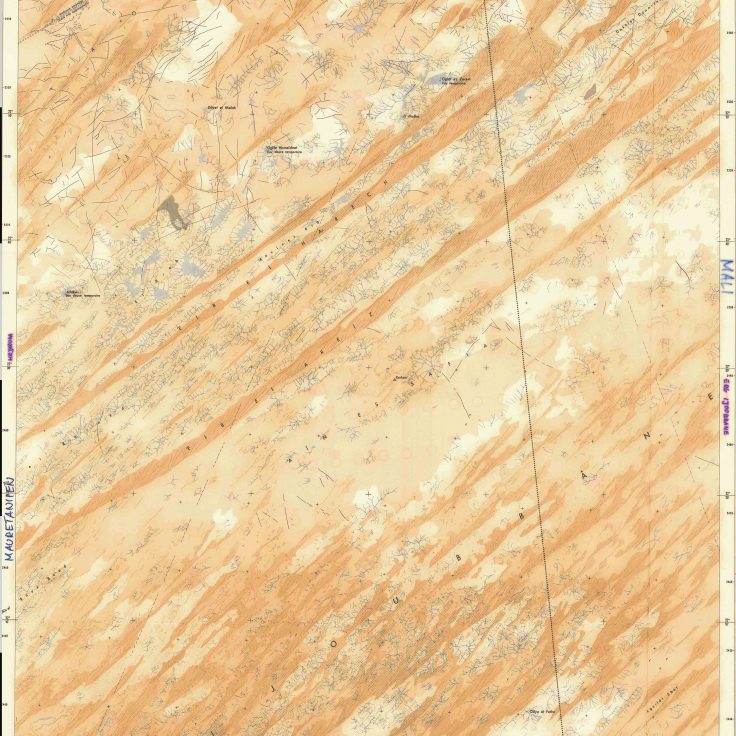

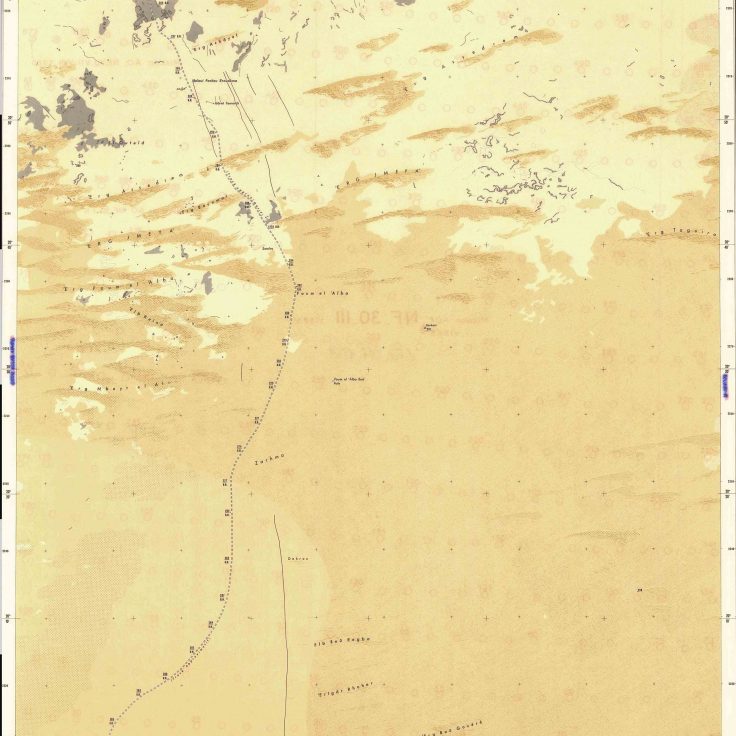

| 2 – Guettatira. The dune-fields of Erg Chech extends from eastern Mauritania to southwest Algeria for nearly 1000 km. The Malian part shown on this map has widely spaced longitudinal dunes, formed parallel to prevailing winds, between which meteorites are sometimes found. Giant ergs (Arabic for sand) like Erg Chech are actually much less common in the Sahara than flat gravel-covered plains called regs (stone) or barren surfaces of consolidated material known as hamadas (rock). |

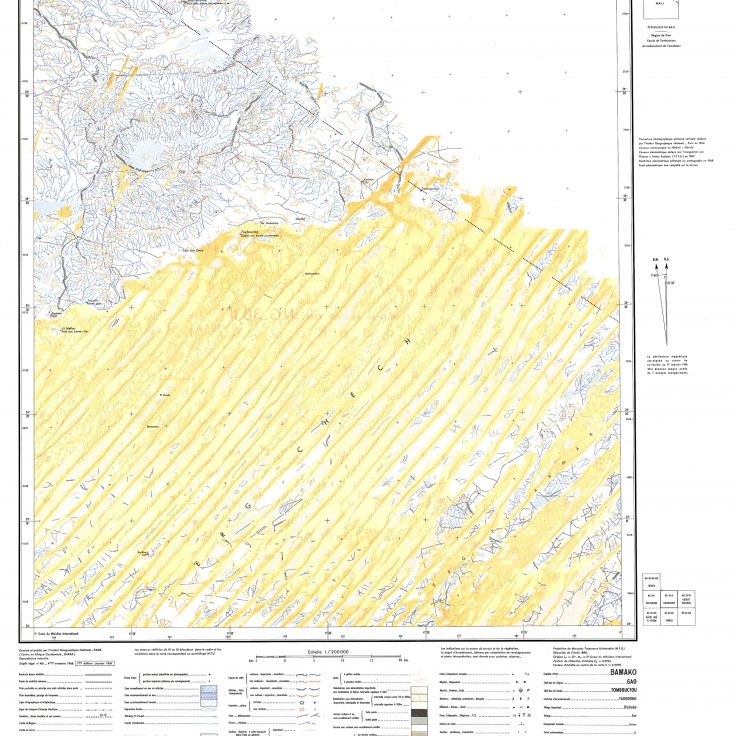

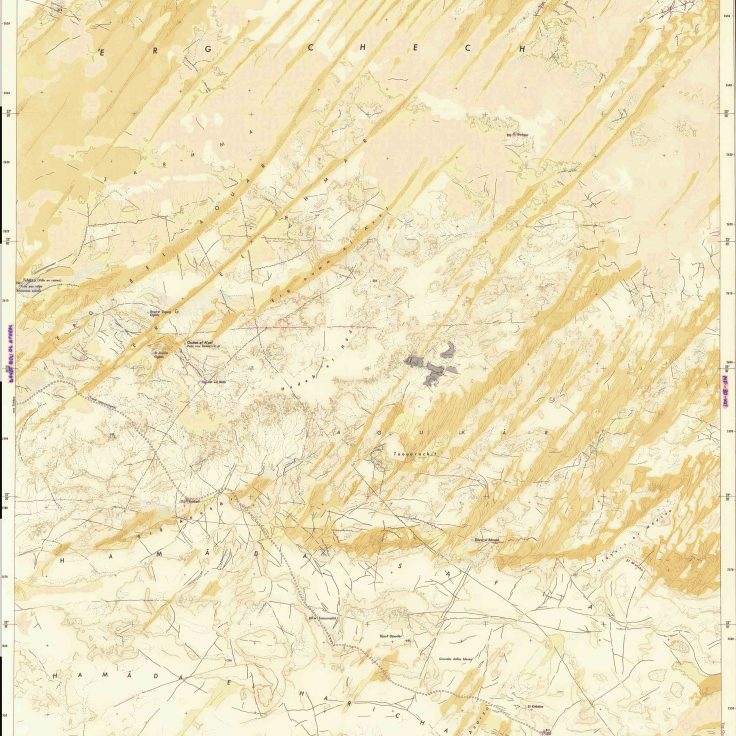

| 3 – Toufourine. The Toufourine well gives its name to this map in the far north of Mali. In this hyper-arid region, the underlying bedrock is visible, in places, between the large longitudinal dunes of Erg Chech. Unlike the map, the massive dune-field of Erg Chech does not stop at the Algerian border but extends over more than 500 km towards Reggane and Adrar in Algeria. |

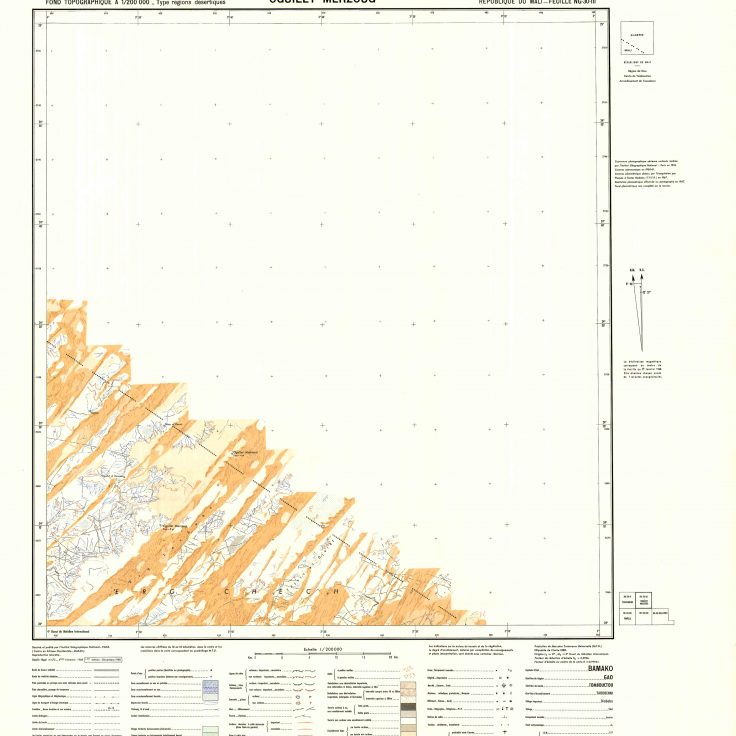

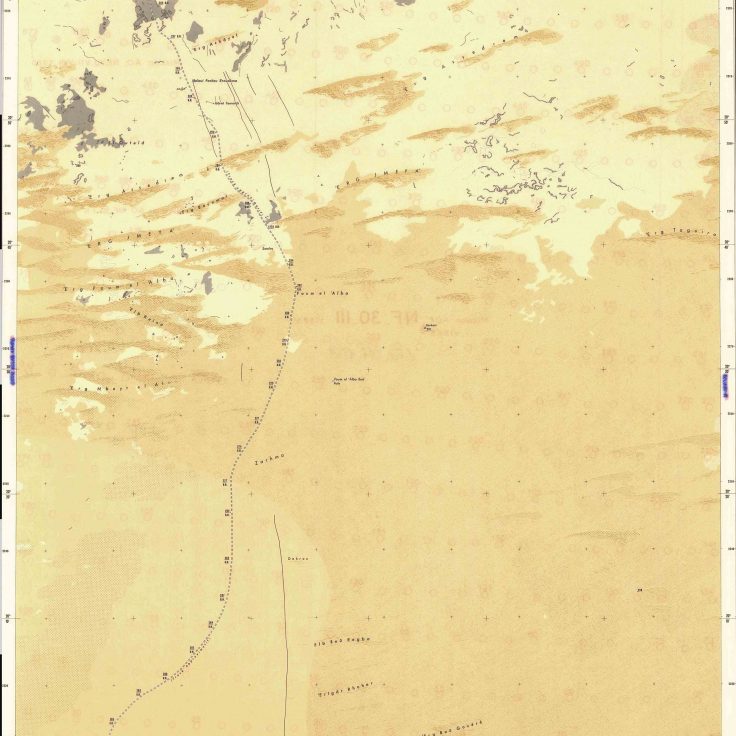

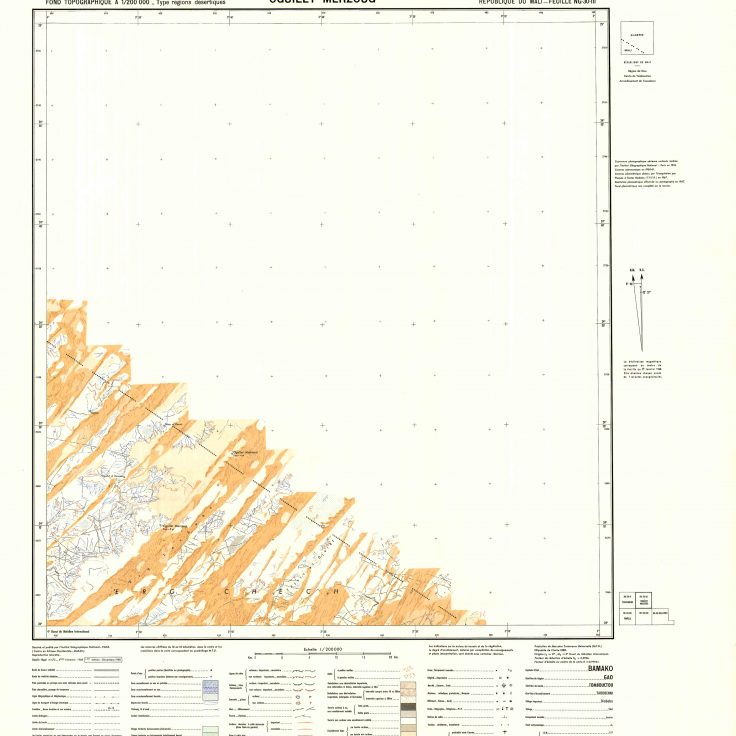

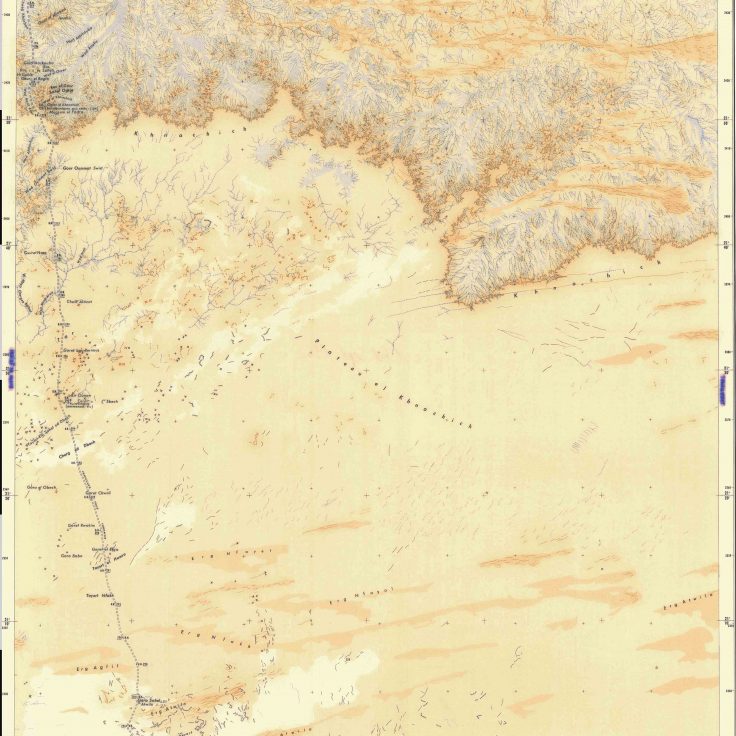

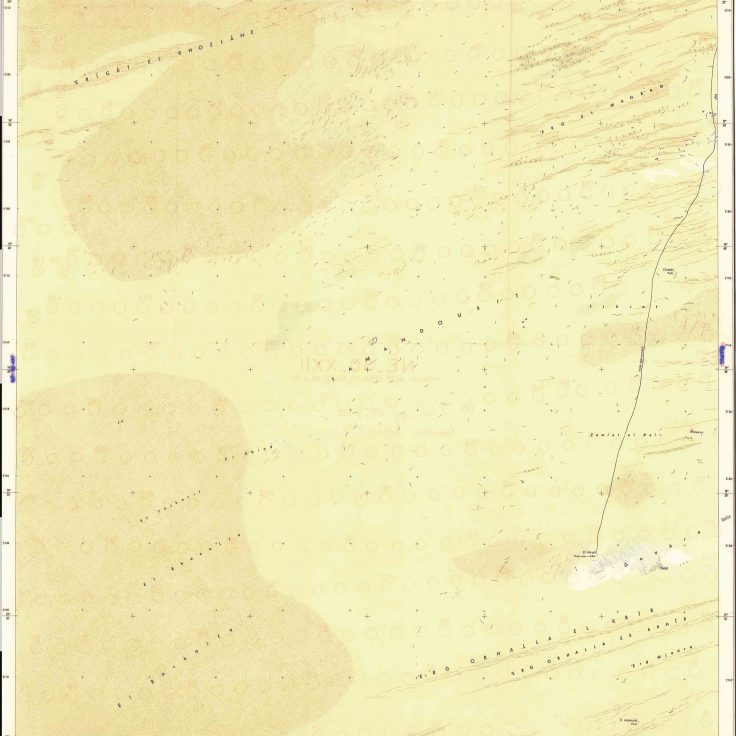

| 4 – Oguîlet Merzoug. This 1968 topographical map of Oguîlet Merzoug in northern Mali is also a political map. Its most impressive feature is the international boundary between Mali and Algeria, which runs through Erg Chech. This portion of the border remained poorly demarcated until the 1980s. More than 1,400 km north of Bamako, the topography comes to an abrupt halt at the border. The national territory is an island surrounded by white spaces on the map. |

| 5 – Agâraktem. The Agâraktem well, which gives its name to this map of western Mali, is actually located in Mauritania. A rudimentary track runs along the southern edge of Erg Chech, one of the largest dune-fields of the Sahara. The track detours to reach the fresh and permanent water of the well. |

| 6 – Dâyet Boû El Athem. No human settlement has been observed in this arid region of northern Mali, only a few wells. In the absence of localized resources or major trade routes, human occupation is nomadic and transient. Concepts of space and territory are operationalized differently in the Sahara. Nomadic space is produced by the seasonal alternation of activities, rather than by strict boundaries between political entities. |

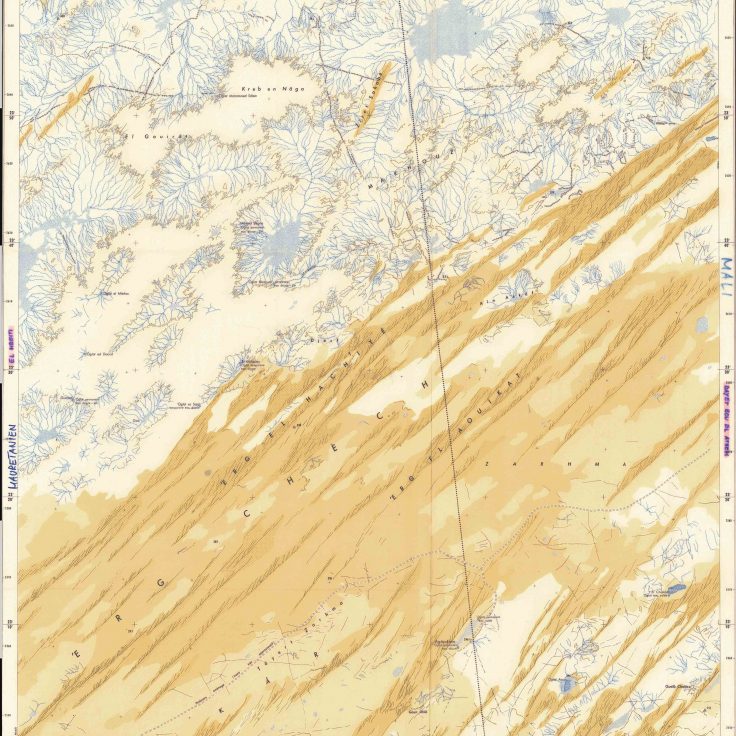

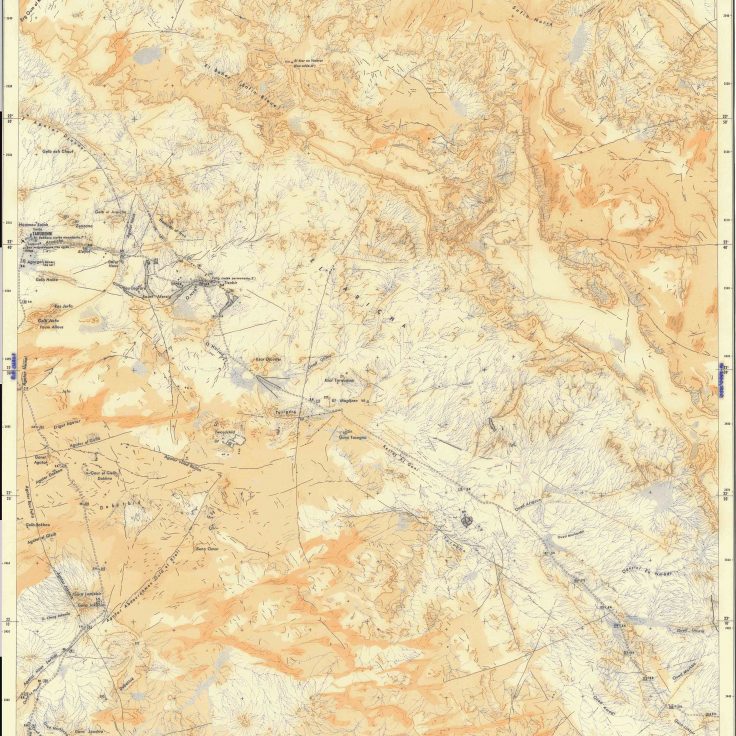

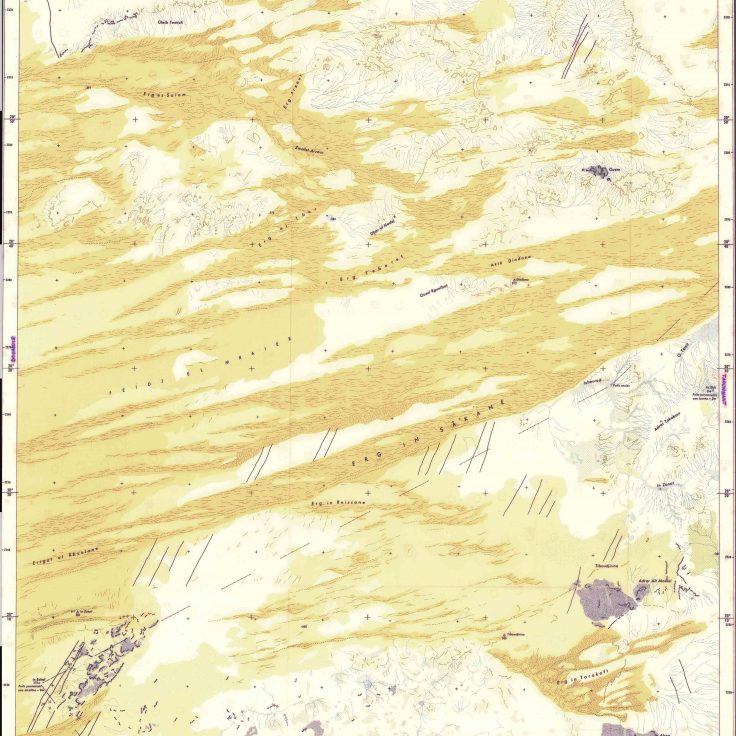

| 7 – Trhâza. The ancient mining center of Trhâza (also Teghaza or Terhazza), in the far west of the map, played a major role in trans-Saharan trade. Now in ruins, the salt-mining center was connected both to Sijilmassa in today’s Morocco and to Timbuktu in today’s Mali to the south. Teghaza was abandoned at the end of the sixteenth century when salt production moved to Taoudenni. To the south, the dunes meet the rocky Hamada Safia. Boundaries between sandy and rocky landscapes are often sharp in the Sahara, because the wind passing from one surface to another speeds up, stripping finer materials from the surface. |

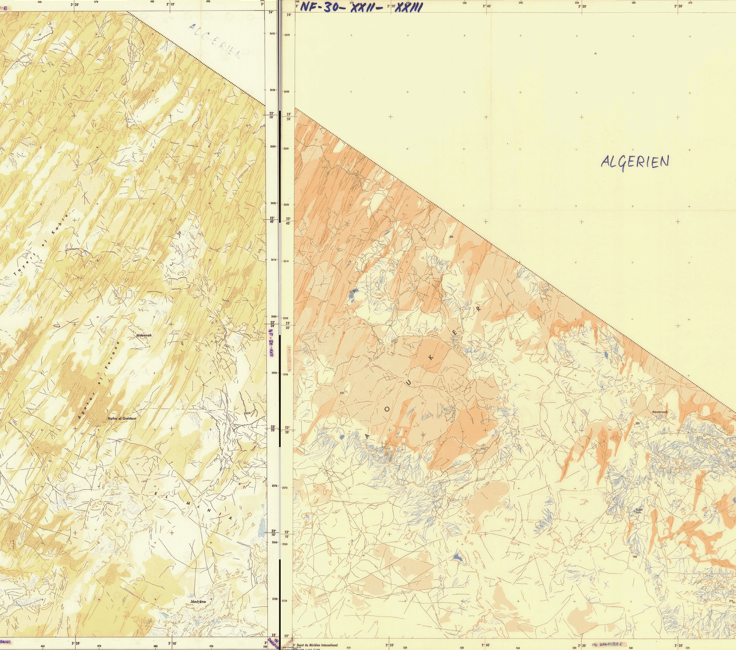

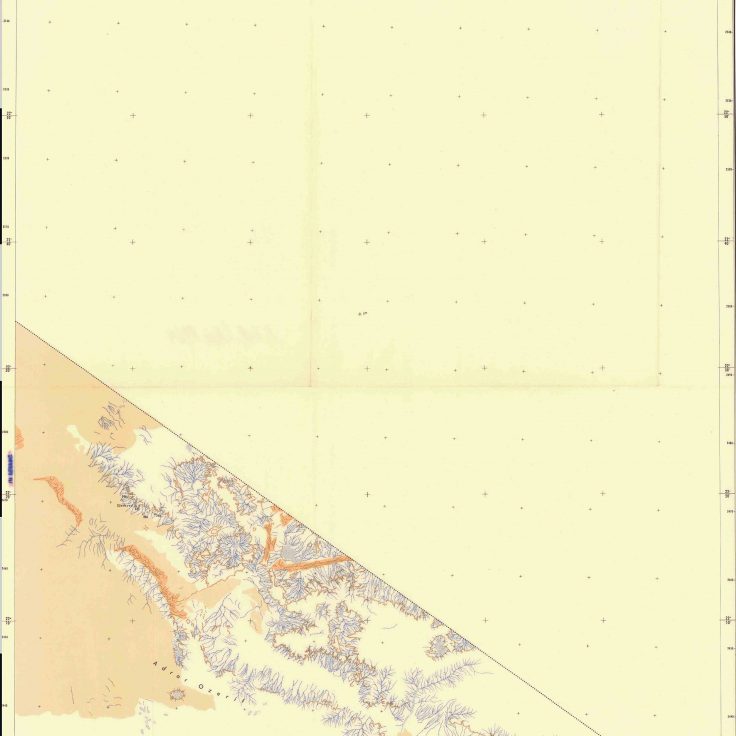

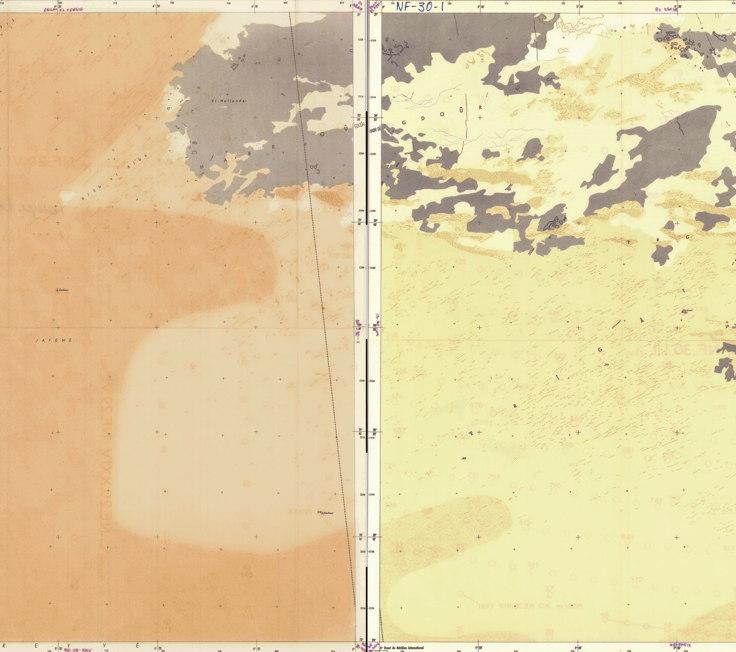

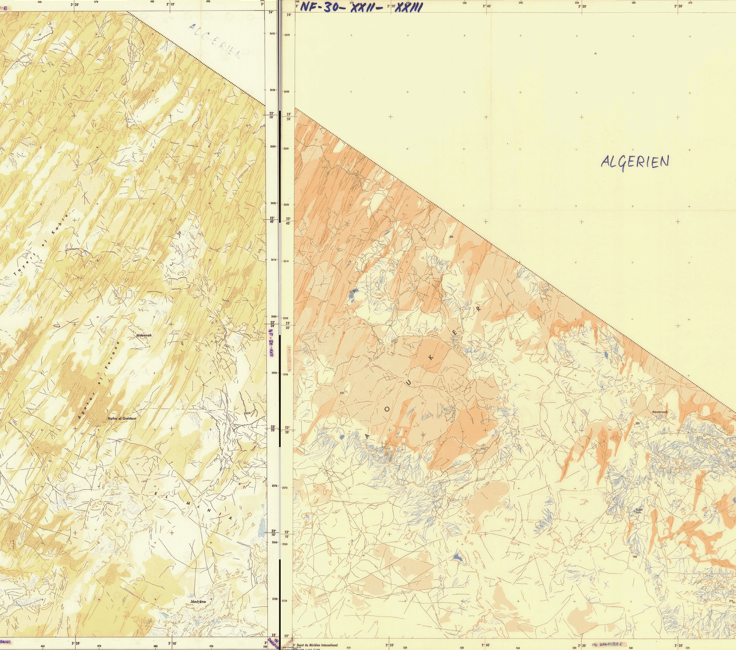

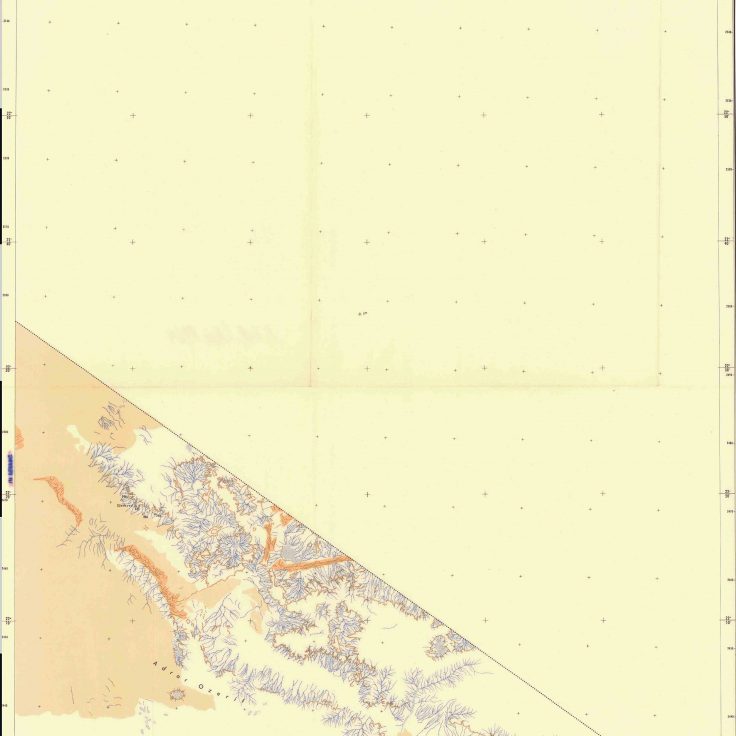

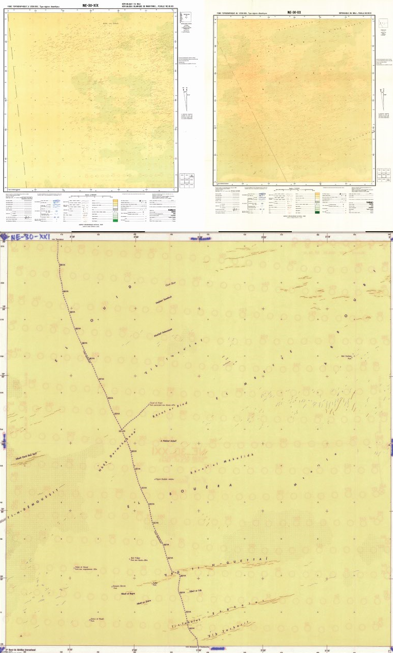

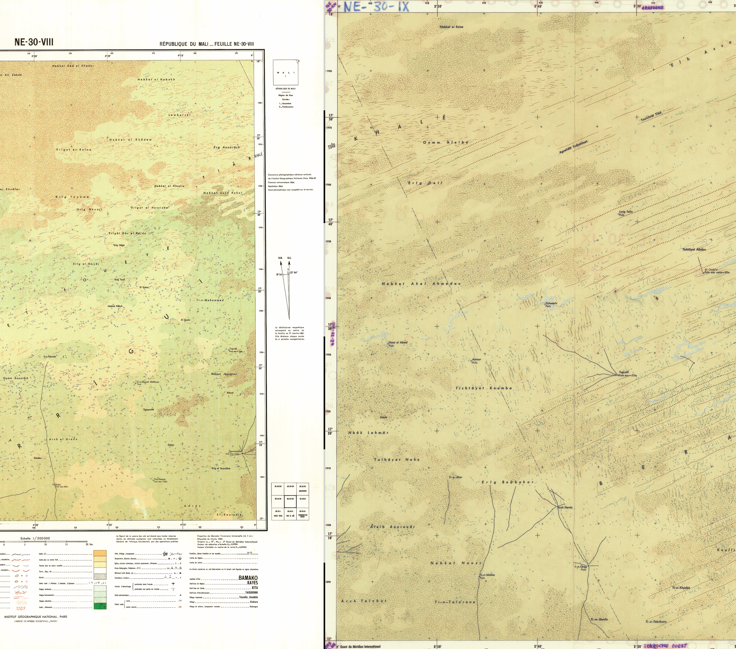

| 8/9 – NF–30–XXI/ NF–30–XXII–XXIII. These maps of the far north of Mali drawn by the French National Geographic Institute (IGN) in the mid-1950s have no proper name, only a code. No inhabited places or major topographical landmarks can be seen in this region twice the size of Qatar. |

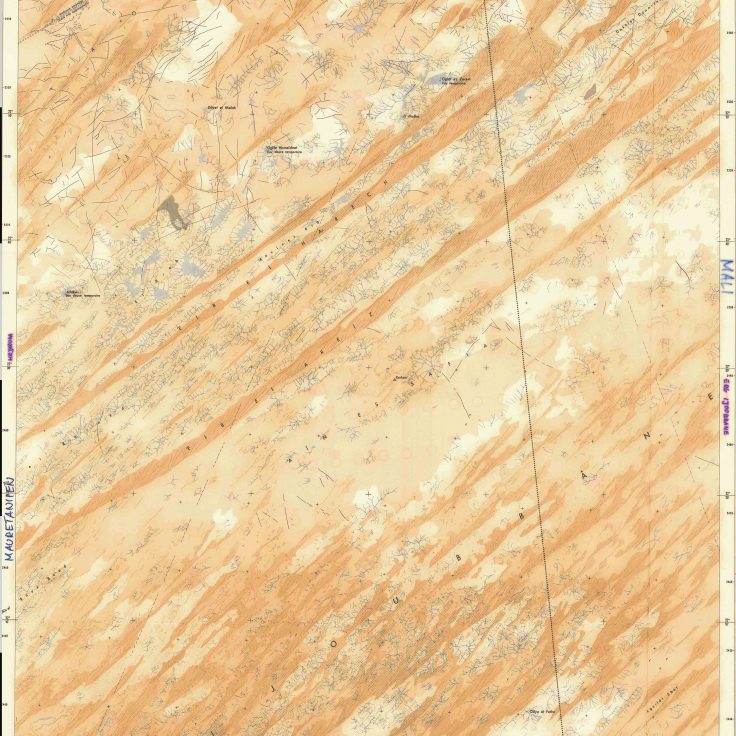

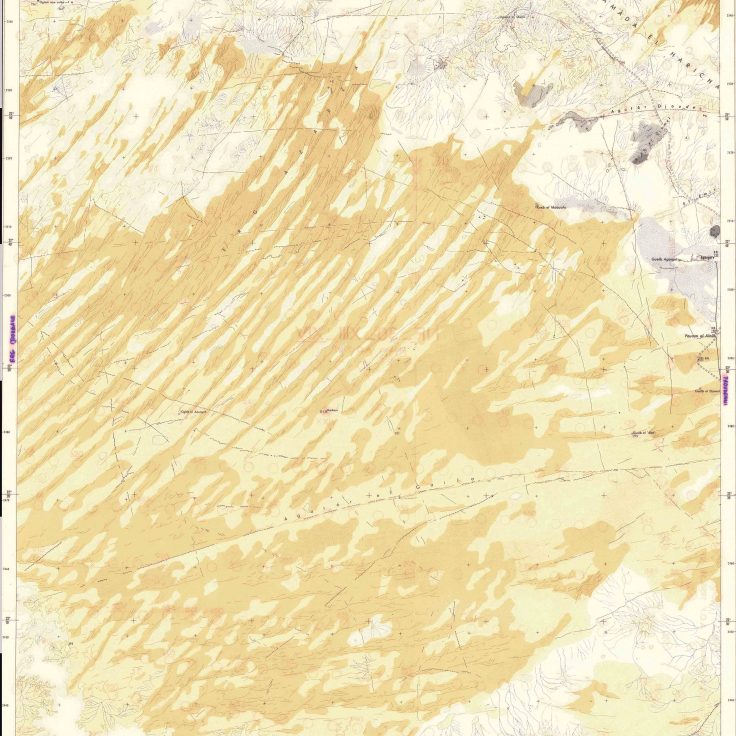

| 10 – Oglât Hameïdnat. The long, parallel dunes of Erg Ijoubbâne stretch from eastern Mauritania to the outskirts of Taoudenni in Mali over more than 300 km (map #11) . |

| 11 – Erg Ijoubbâne. The name Kerkour, which appears three times on the map along with an altitude, refers to human-made piles of stones on high ground similar to cairns (map #10). |

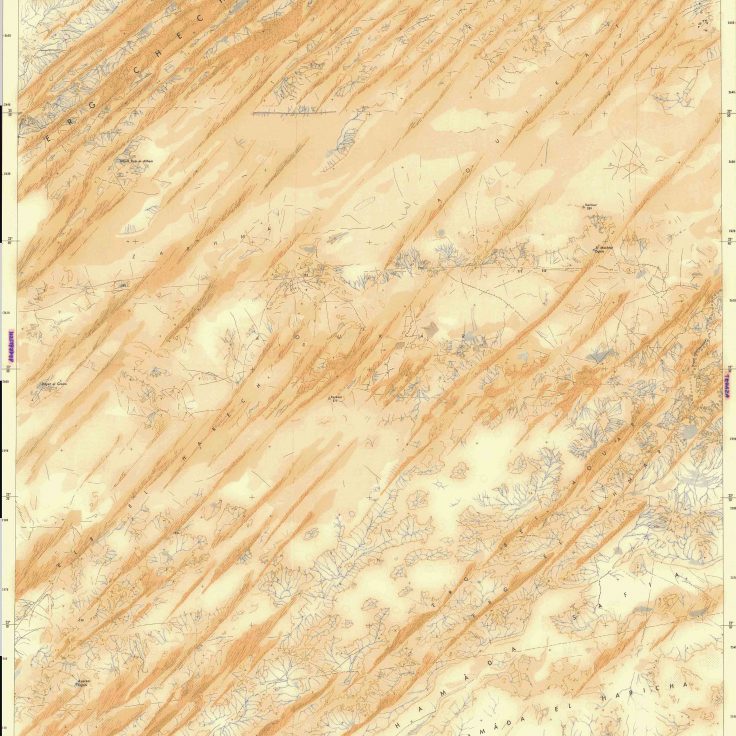

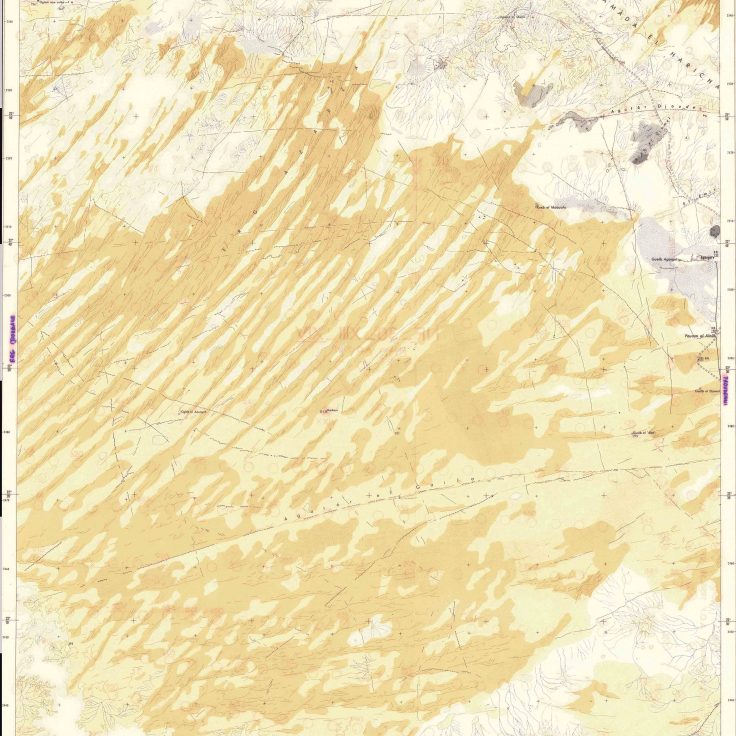

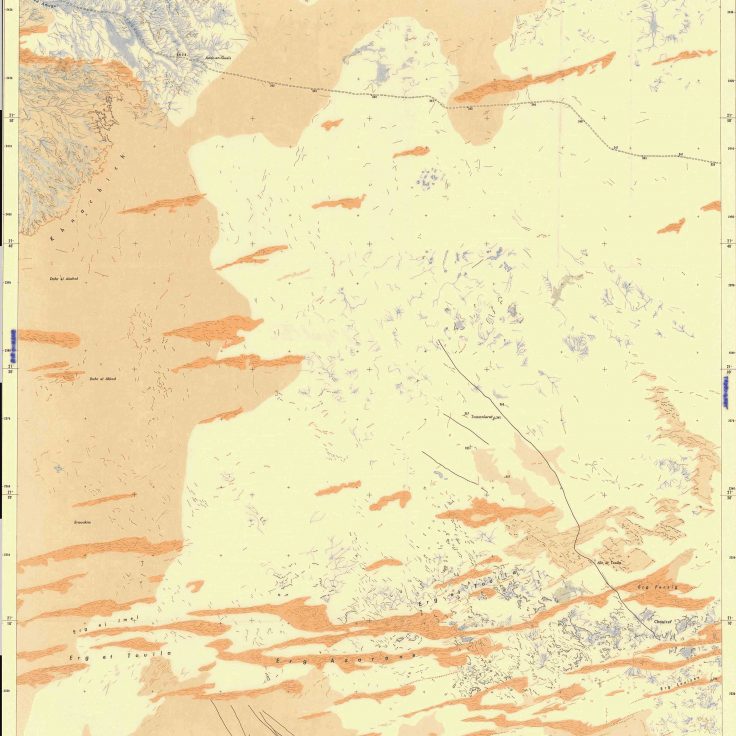

| 12 – Bir Chali. The rough track linking the abandoned salt mines of Trhâza to Taoudenni cuts the NE corner of this map of Bir Chali. The Chali well (bir in Arabic) and its salt water is visible at the extreme NW of the map. Travelers using this road avoid the wide sandy expanses of Erg Azarza as well as the rocky plateau of Hamada El Haricha. |

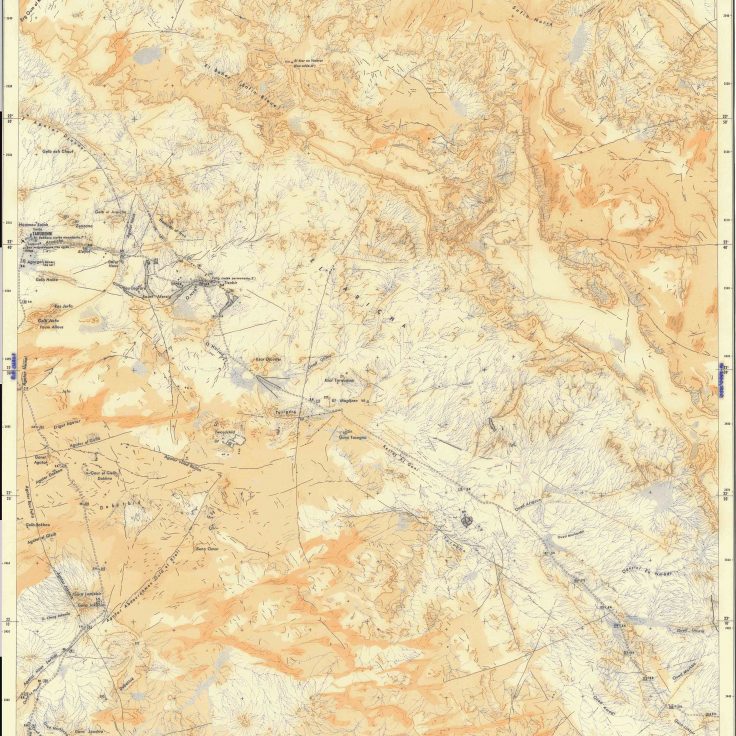

| 13 – Taoudenni. Taoudenni has played a key role in the Trans–Saharan route between Sijilmassa and Timbuktu since at least the fifteenth century. The caravan that seasonally brings the salt to the south is known as the Azalai. It takes a camel driver 15 days to reach the Taoudenni salt mines from Timbuktu. The mines were used as an open–air prison for the political opponents of Malian President Moussa Traoré. The area around Taoudenni is dotted with longitudinal dunes leaning against rocky peaks and spectacular rocky ridges called agators. Both were photographed for the first time by French aviators in the 1930s. |

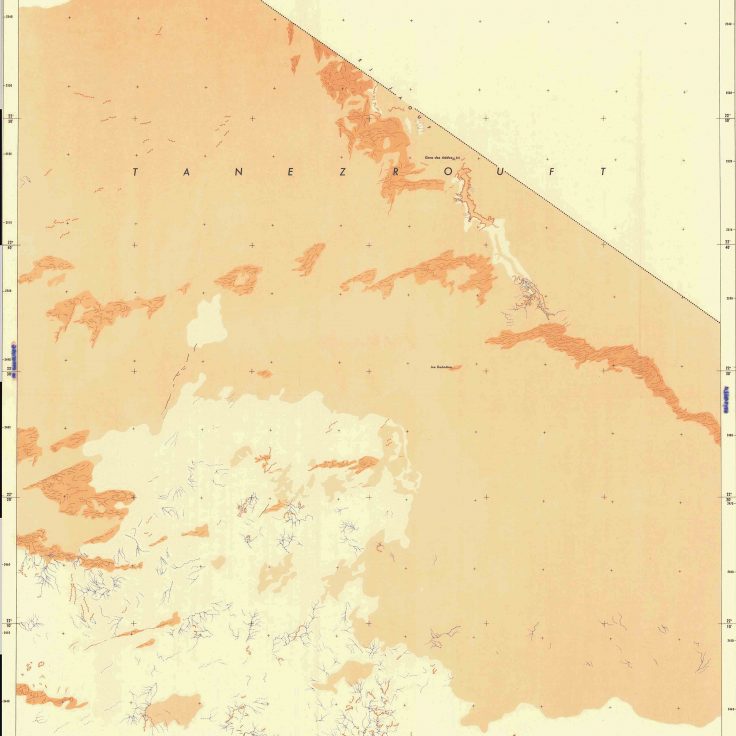

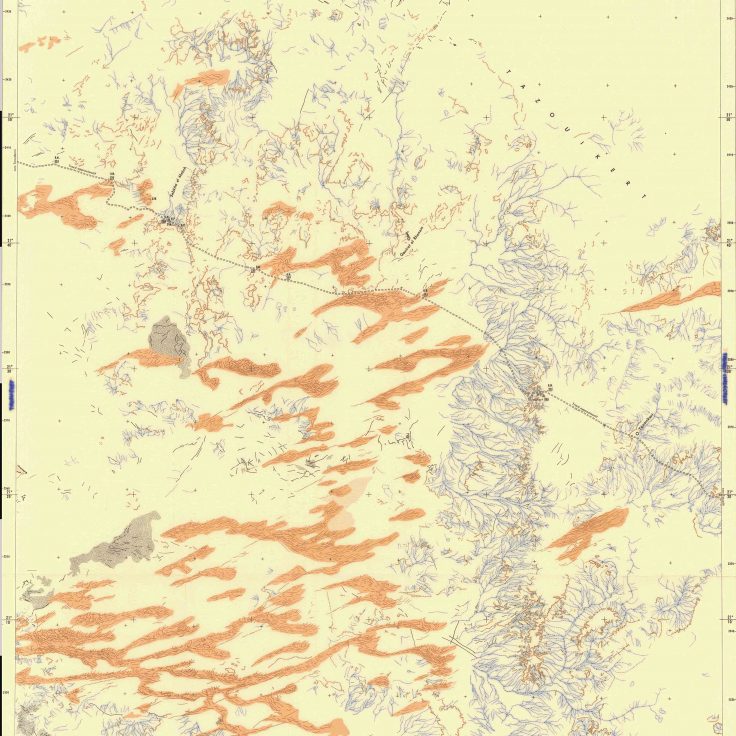

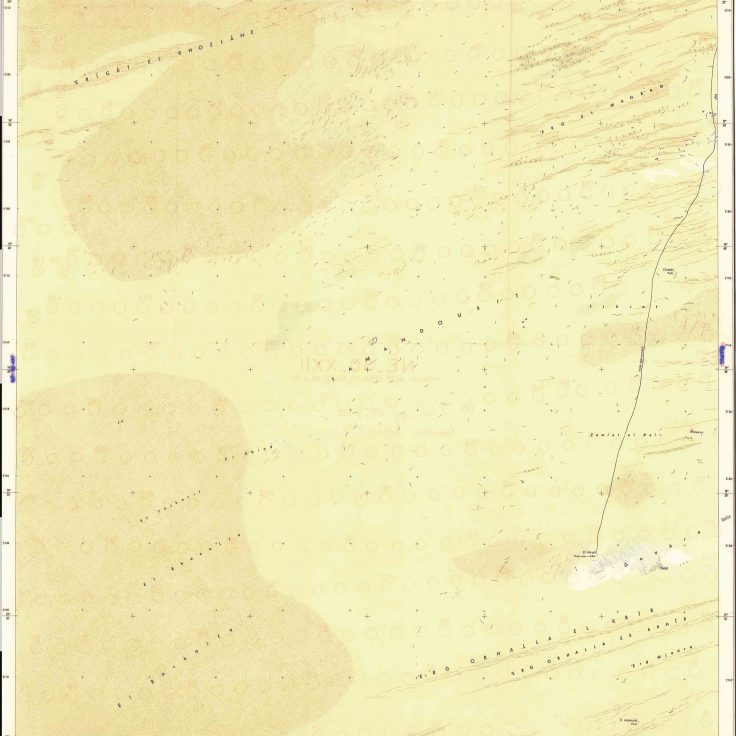

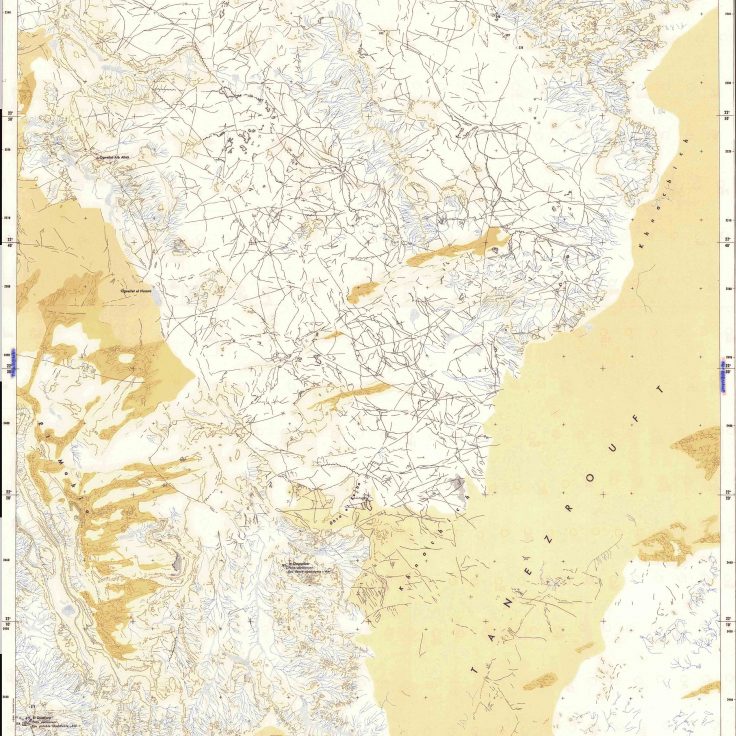

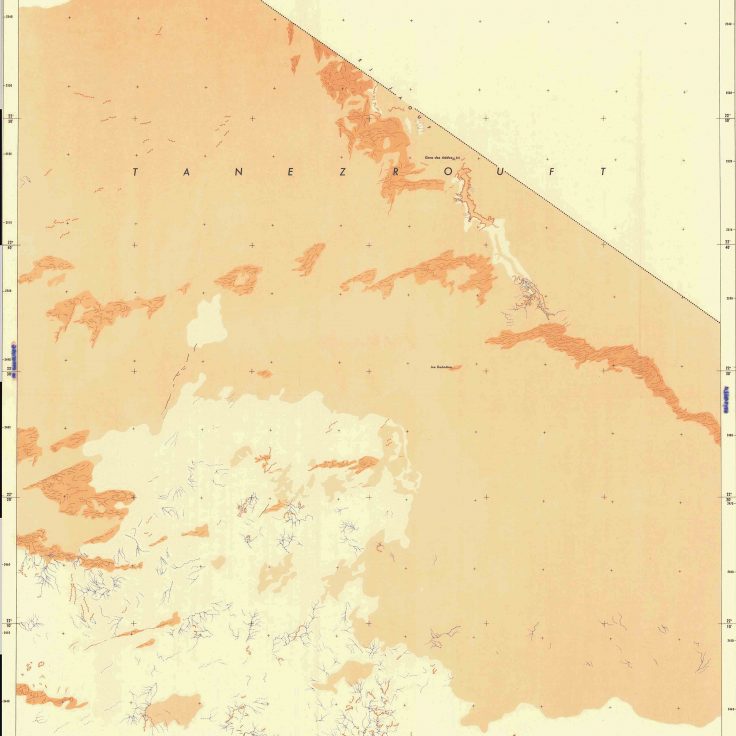

| 14 – In-Dagouber. The southern portion of the Tanezrouft is shown on this map of In-Dagouber. Théodore Monod was the first scientist to cross this desolated area of the Sahara in 1936. His book Méharées: Explorations au Vrai Sahara is dedicated to the camel and the goat, “the only two victors of the Sahara”. While the former serves as a means of transport, the latter’s skin keeps water fresh during 400 km crossings without a well. |

| 15 – In-Debnâne. The Tanezrouft is one of the least inhabited and flattest regions of the Sahara. On this map of In-Debnâne, the most important topographical landmark is the Gara des Addax (an addax is a white antelope), a modest hillock rising to 341 m above sea level. |

| 16 – Djedeyed. In this Malian region bordering Algeria, the most striking feature is the omnipresence of temporary watercourses, which form a dense network downstream of the tabular reliefs. Although hyper-arid regions receive very little rain, torrential rainfall can be very dangerous in the Sahara. Swiss explorer Isabelle Eberhardt drowned in a flash flood at Aïn Séfra, in the Algerian Sahara, in 1904. More recently, devastating flooding destroyed the city of Derna in eastern Libya. |

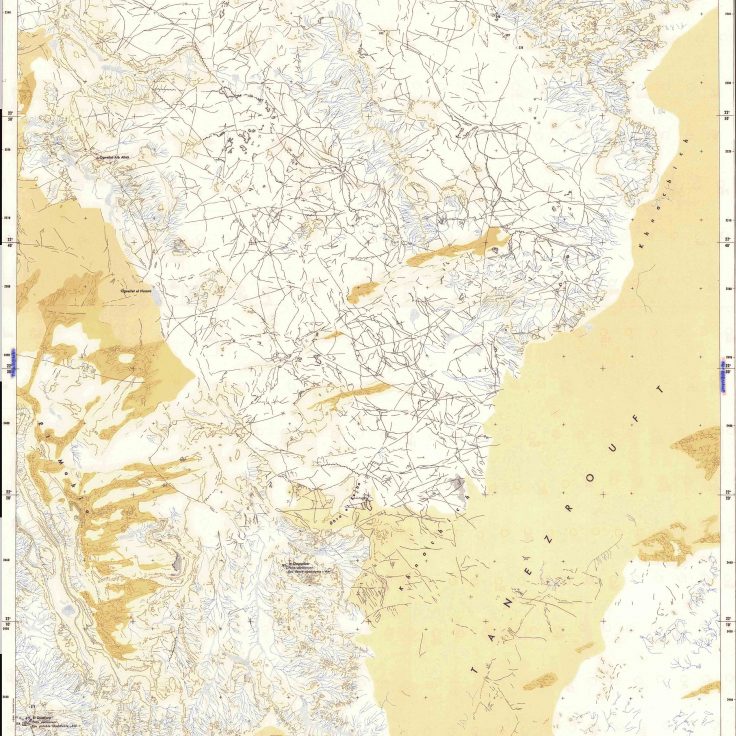

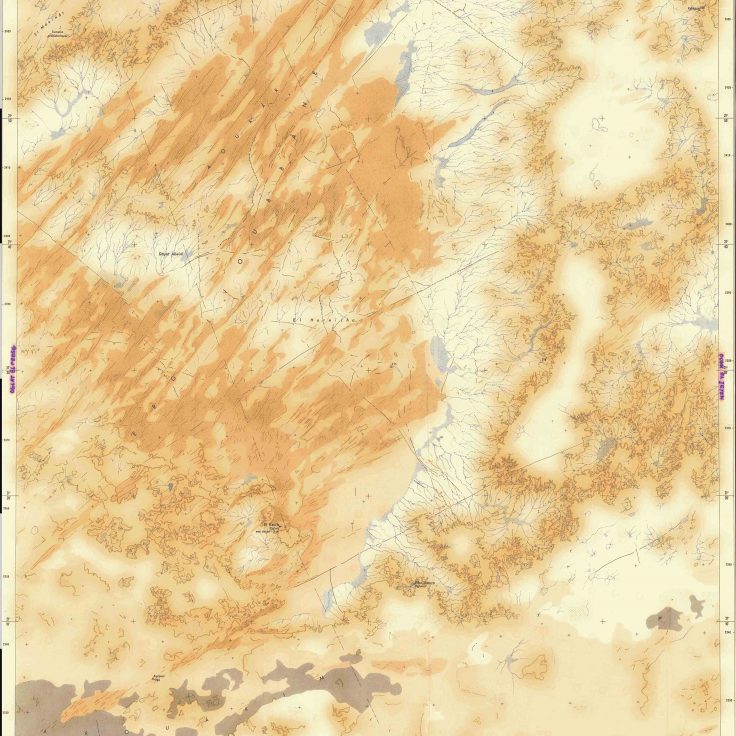

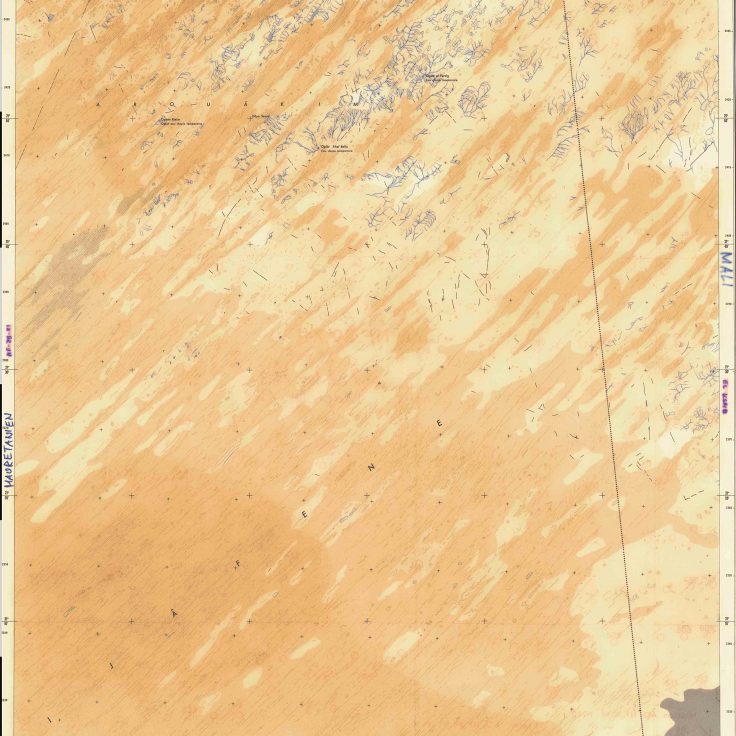

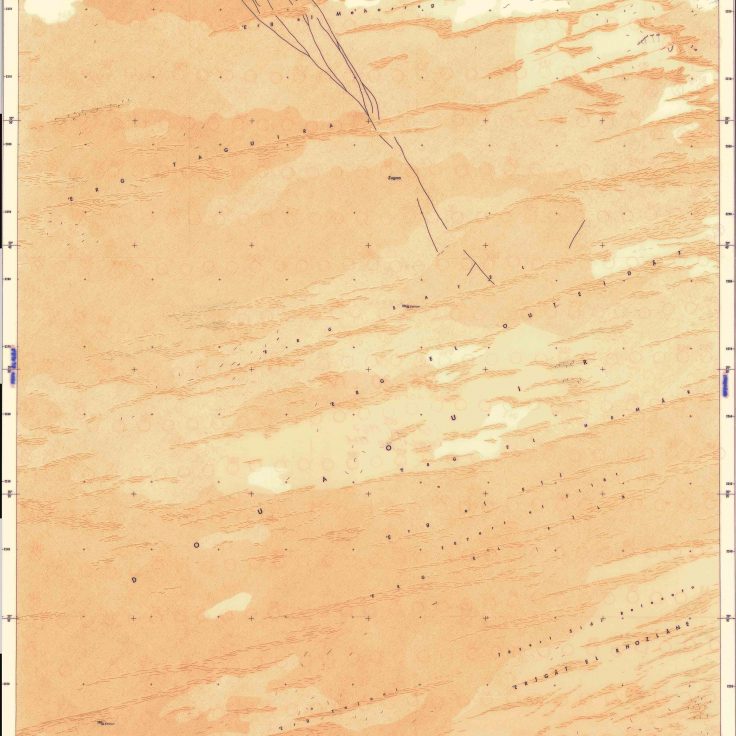

| 17 – Oglât el Fersig. Much of the map of Oglât el Fersig is occupied by Erg Ijâfene, whose longitudinal dunes extend for more than 400 km into neighboring Mauritania. Théodore Monod called this vast, uninhabited region Majâbat al-Koubrâ, a term borrowed from the Arab geographer Al Bakri, meaning "a great emptiness where one merely passes through". In 1956, Monod was the first scientist to travel from Ouadane to Araouane, a journey of 900 km without wells. This part of NE Mauritania and northwestern Mali is also called, erroneously according to Monod, El Djouf or Empty Quarter. |

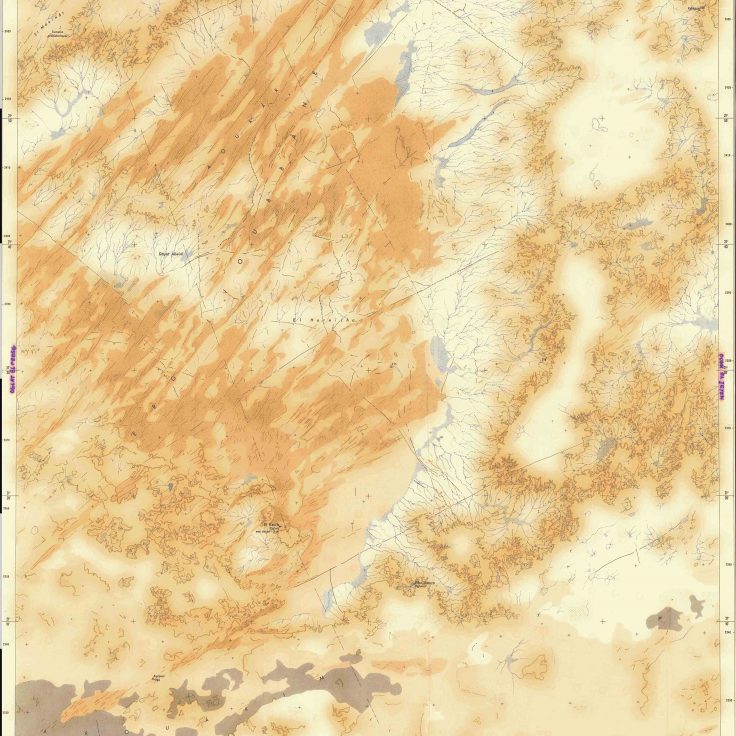

| 18 – El Ksaïb. Bir El Ksaïb was an important oasis on the Trans-Saharan roads that connected the Senegambia to the Mediterranean coast in the Middle Ages. It was the first oasis that caravans crossing the desolate Majâbat al-Koubrâ reached after ten full days without a well to water their camels. The El Ksaïb region is dominated by Erg Oubbane and Erg Aoukar. The location of these large dune fields is determined by ancient hydrographic conditions. The sediments that make up the dunes were deposited during wetter periods by rivers that have now disappeared. The constant wind shapes the dunes depending on its strength and orientation. |

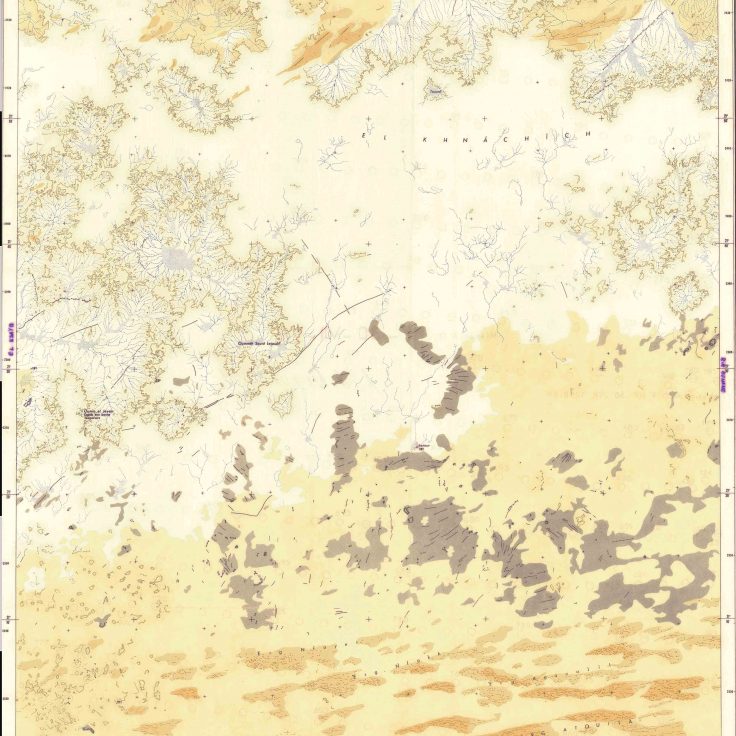

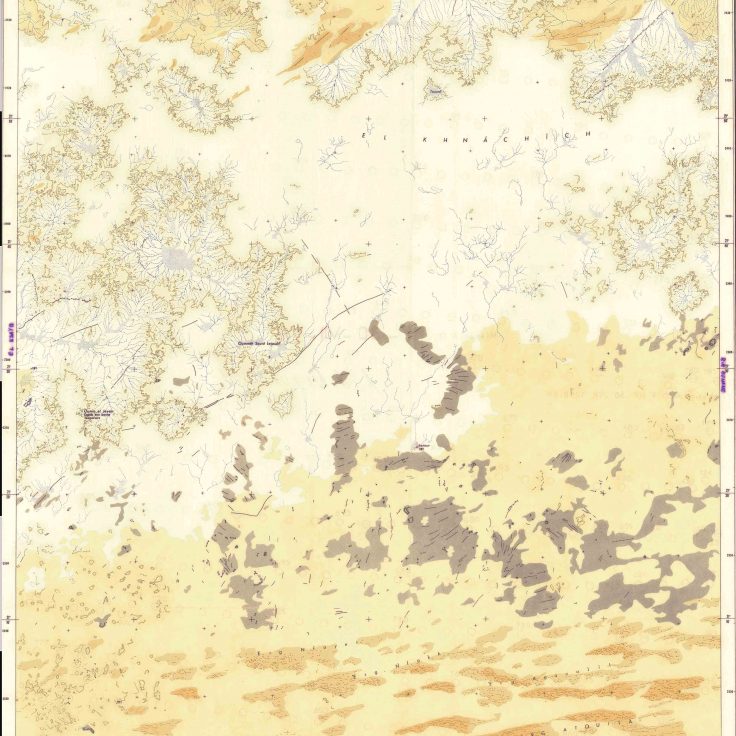

| 19 – Oumm el Jeyem. This map shows the southern part of the El Khnachich cliff, which surrounds the Taoudenni depression, from El Ksaïb in the west to El Guettara in the east, over more than 300 km. Several small endoreic basins are visible in the northern part of the map. |

| 20 – Bir Ounane. Aïn, bir, oued, kori, dallol, hassi, anou, guelta, melzem, daya, iriji, oglât, taghada, ajaar, bat’ha, tamouret: The Sahara is punctuated with names of springs, wells, and temporary rivers. Access to water has required considerable investment on the part of Saharan populations, often using slave labor. The most spectacular example is the digging of the foggara in the Adrar region of southern Algeria. This network of underground pipes collects water from the mountain ranges and carries it to the oases on the plains. |

| 21 – Tamanieret. The eastern part of the El Khnachich cliff is visible on this map of Tamanieret, located 200 km SE of Taoudenni. The cliff, composed of quartzite and white sandstone, marks the southern and eastern boundaries of the Taoudenni basin, one of the largest sedimentary basins in Africa. Like all sedimentary basins, the Taoudenni basin could conceal oil or gas. So far, however, drilling has made no significant discoveries. |

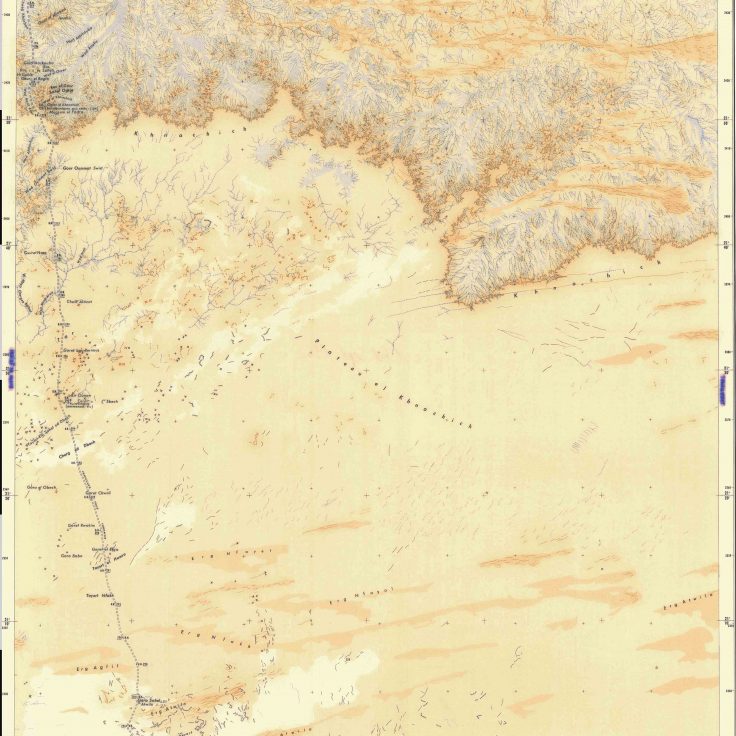

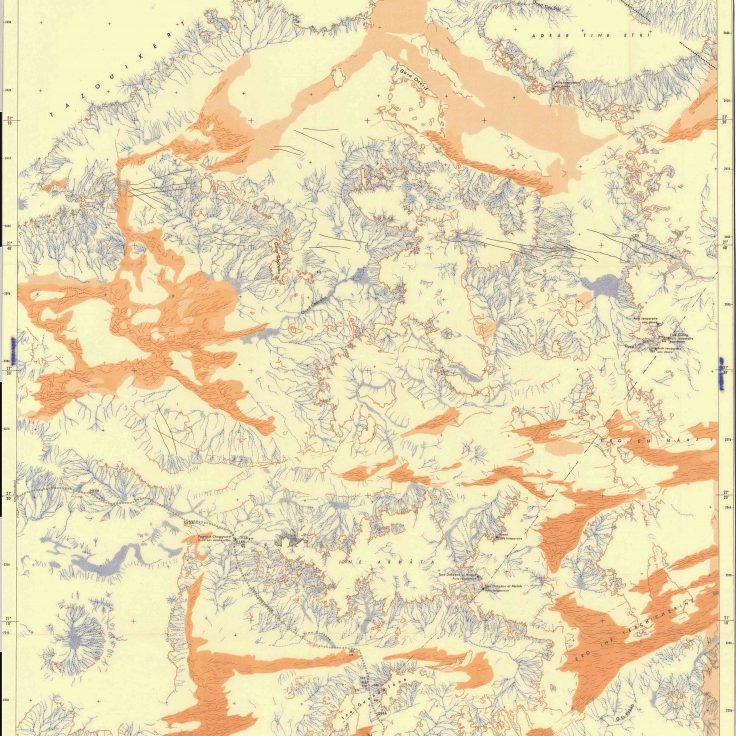

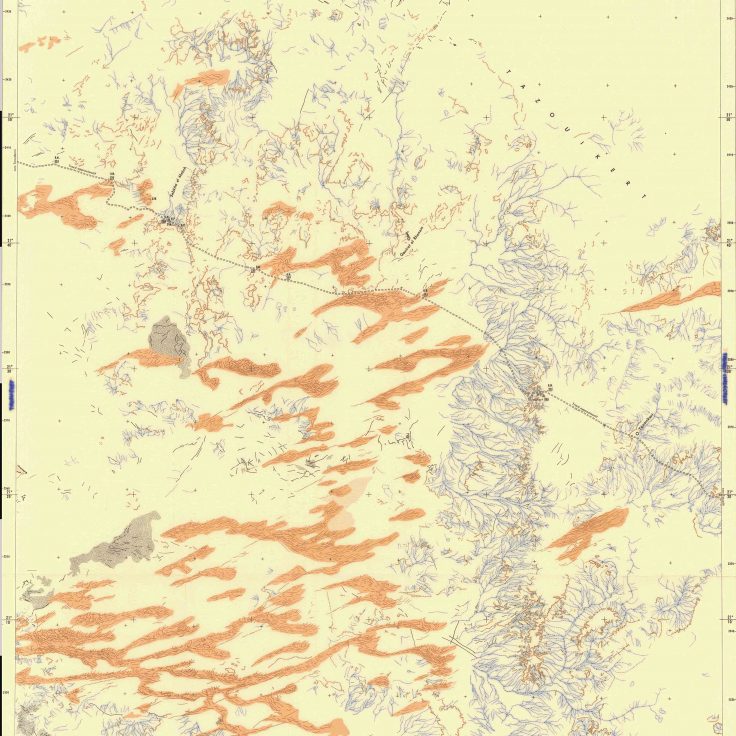

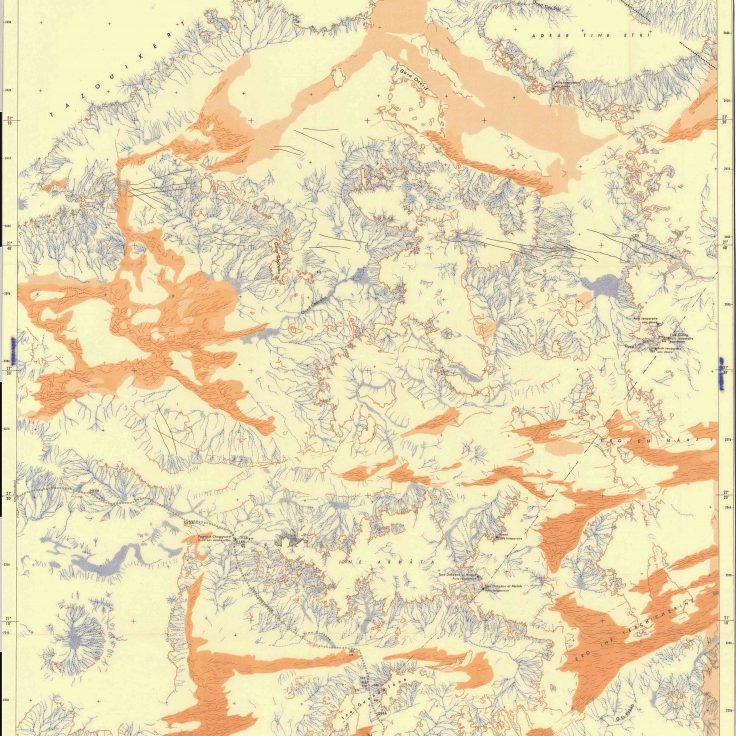

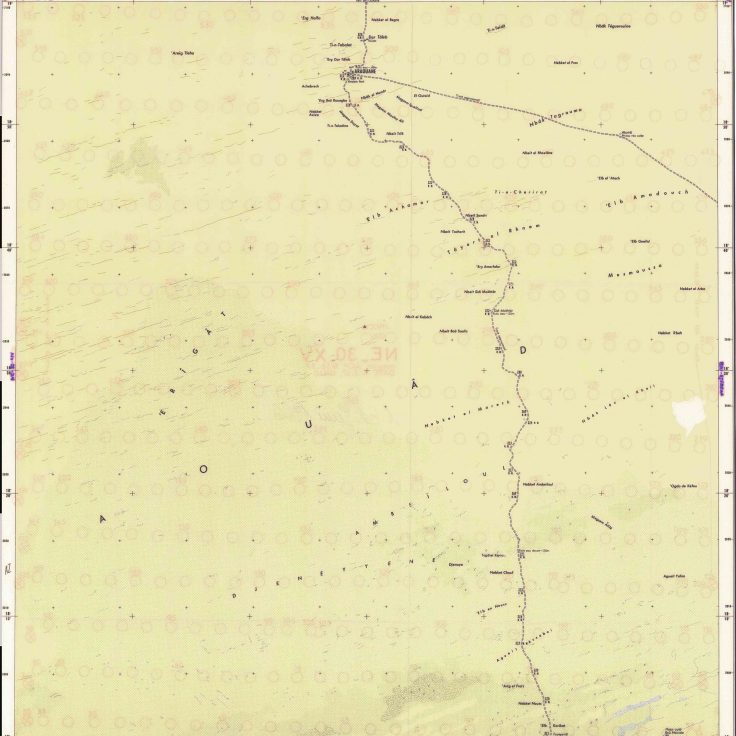

| 22 – Tazouikert. Few travelers venture along the 575-km-long track between Tessalit and Taoudenni, a desolated area without any permanently inhabited places or wells. At Tazouikert, the rough track descends from the rocky plateau before continuing between stretches of sand. Since the mid-2000s, Mali’s far north has been a haven for traffickers and religious extremists, both of whom are closely linked to the nearby Algerian border. |

| 23 – Tagnout Chaggueret. In the desert region of Tagnout Chaggueret, temporary streams called oueds flowing down from the rocky plateaus run up against small ergs occupying the main depressions. Most of the region’s temporary wells are located on the foothills of these low reliefs, with the exception of Tagnout Chaggueret, situated in the middle of an oued, along the track linking Taoudenni to Tessalit. Its fresh water can be drawn from a depth of 10 m |

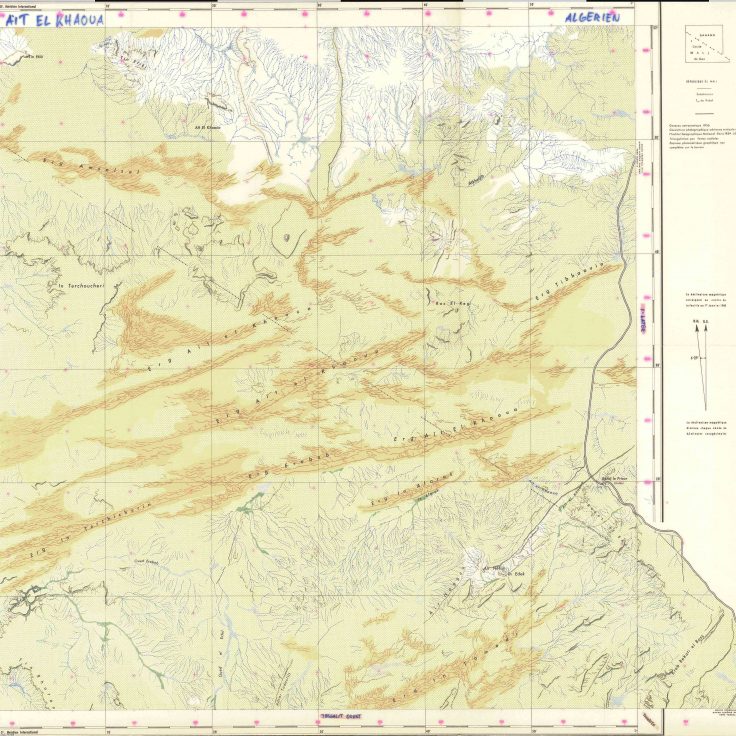

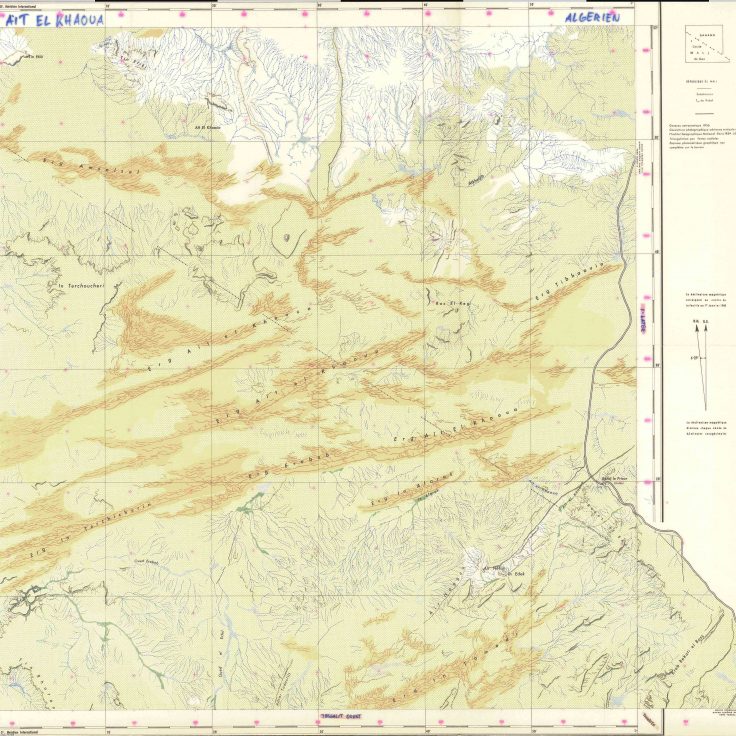

| 24 – Aït el Khaoua. In the early 2010s, Algeria deployed tens of thousands of soldiers along its border with Mali, to prevent incursions from rebels and violent extremists on its territory. Despite this impressive deployment, segments of the border such as Aït el Khaoua, west of Bordj Badji Mokhtar, remain porous. The militarization of the border has done little to disrupt logistical supply lines to extremist armed groups in the Sahel, who have long relied on Algeria for their fuel, flour, pasta, sugar and other commodities. |

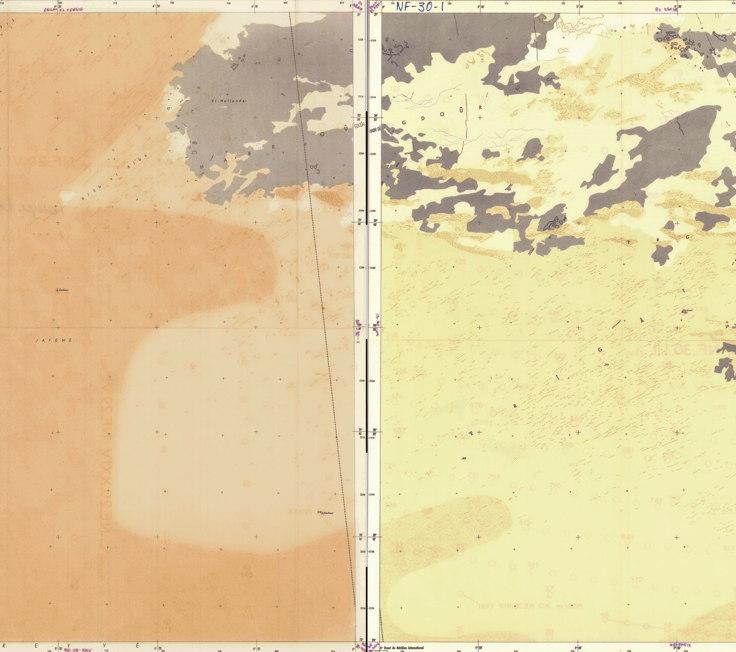

| 25/26 – NF–29–VI/NF–30–I. In NW Mali, the absence of a fixed population does not mean that space is empty. Nomadic societies have developed a different relationship to space than sedentary societies. Due to the impossibility of garrisoning the desert, political power is exercised through control of the crossroads that emerge at the intersection of major trade routes, rather than through control of the territory. |

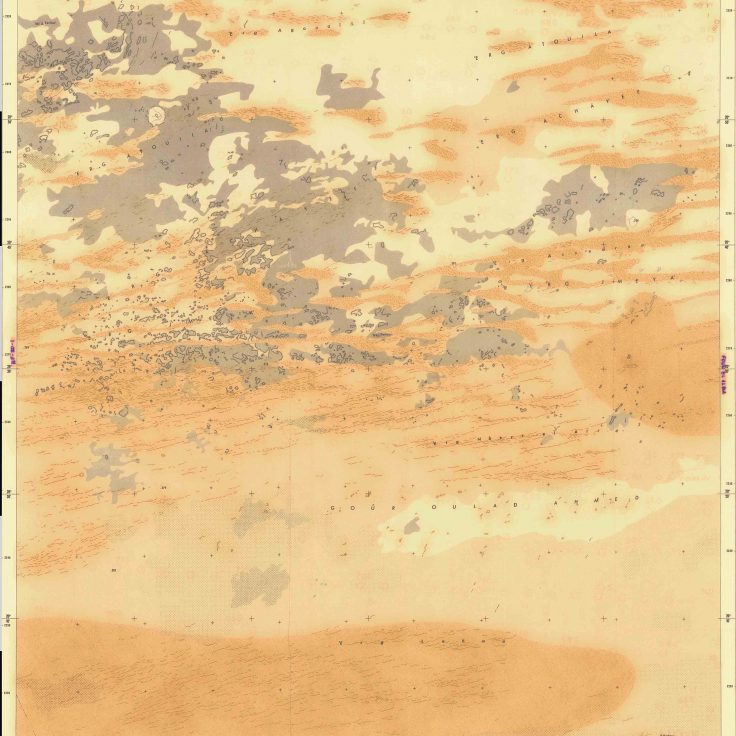

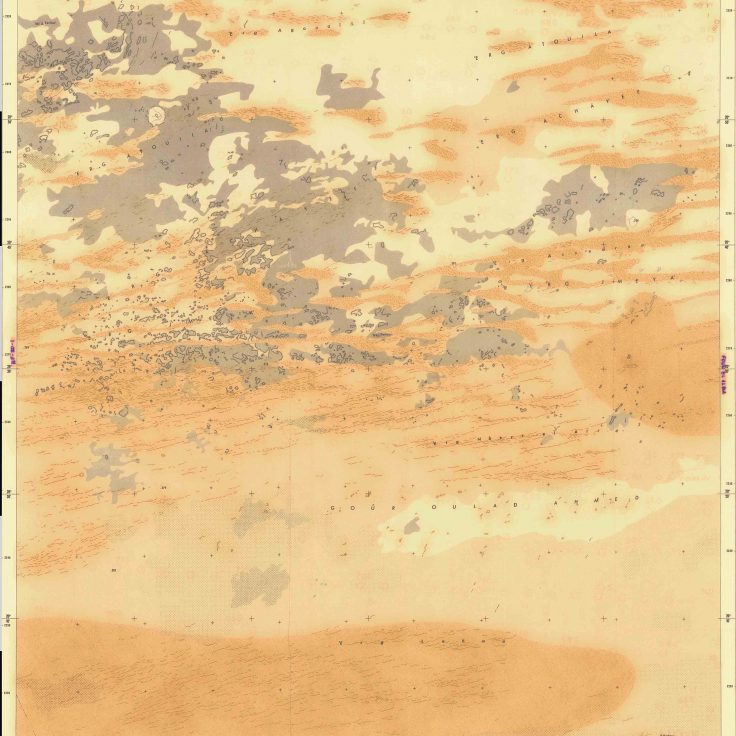

| 27 – Goûr Oulad Ahmed. In this region north of Araouane, sand has almost completely covered the landforms. Crescent-shaped dunes known as barkhanes are particularly numerous in Erg Achayef, in the north of the map, while long, linear dunes are characteristic of Erg Lahma. Goûr Oulad Ahmed probably refers to a boulder balanced on a pinnacle rock (or mushroom rock) formed by aeolian erosion, a common feature in the Sahara. |

| 28 – Foum el Alba. Archaeologists have discovered numerous Paleolithic tools in the interdunal hollows of the Foum el Alba region. These tools bear witness to wetter periods, during which the Sahara was covered by large lakes that have now disappeared. The fauna was typical of Sudanese regions: crocodiles, hippopotamuses, lions, and giraffes rather than camels and goats. |

| 29 – Douaouir. The region of Douaouir in northern Mali is almost entirely covered with large expanses of dunes and sandy plains. The most distinctive features of the map are the long rocky outcrops that cross Erg Taguira perpendicularly, and the pile of stones on high ground (kerkour), which reaches an altitude of 324 m. |

| 30 – Ichourad. The Ichourad region in northern Mali offers a stunning patchwork of sandy and rocky areas. To the east of the map is Adrar Tabakart, a low mountain range with two wells. The southern part of the map is streaked with long, parallel rocky outcrops, which disappear into the sands of Erg In Sâkane. |

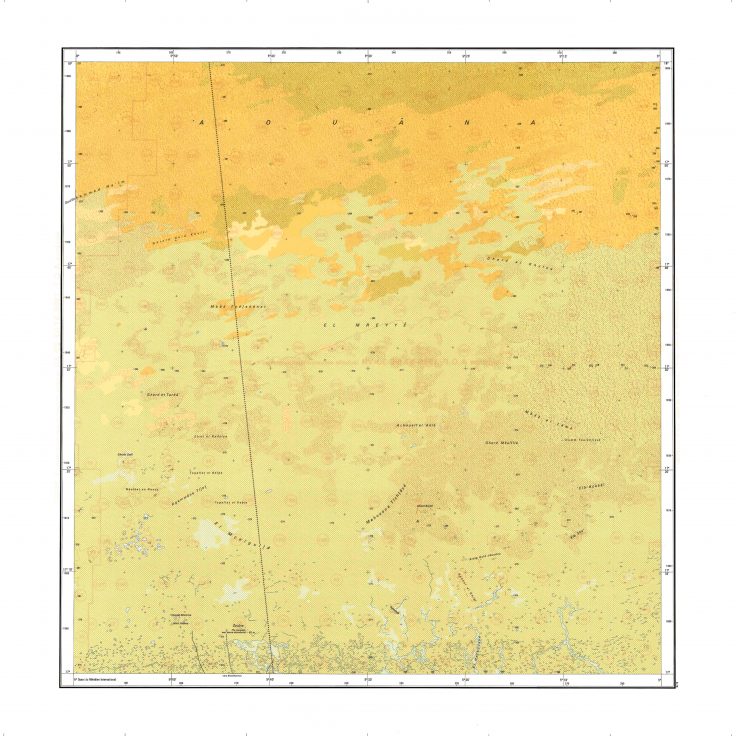

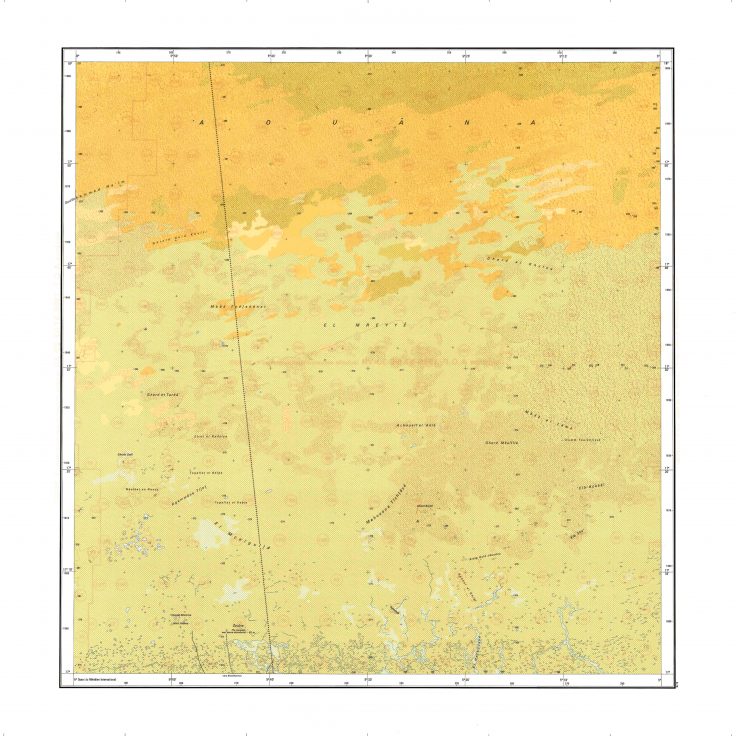

| 34-35-36 – NE–30–XIX/NE–30–XX/NE–30–XXI. These maps show El Mreyyé, an immense sand plain crisscrossed by small, winding dunes less than 5 m high. The track linking Araouane to Taoudenni, used by salt caravans from Timbuktu, crosses it in a straight line. |

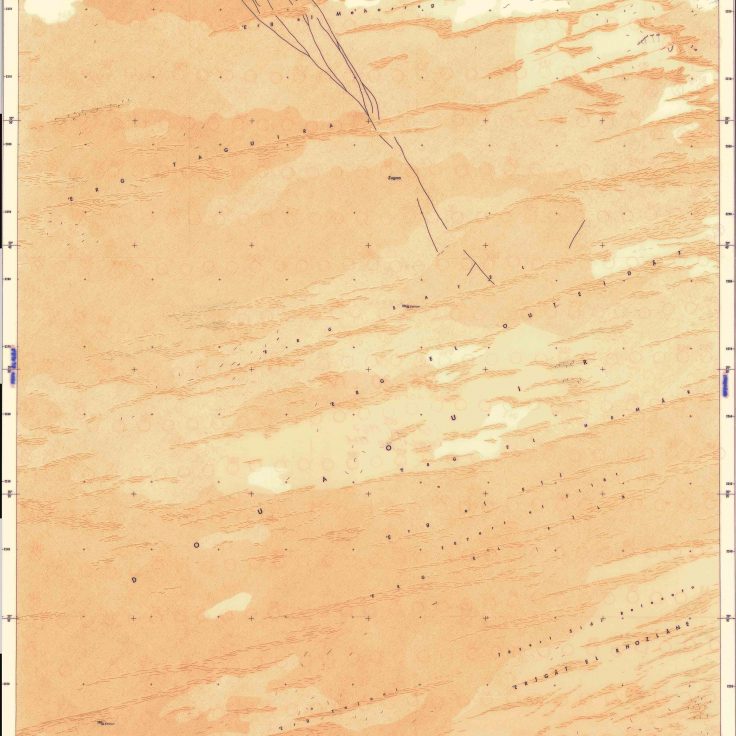

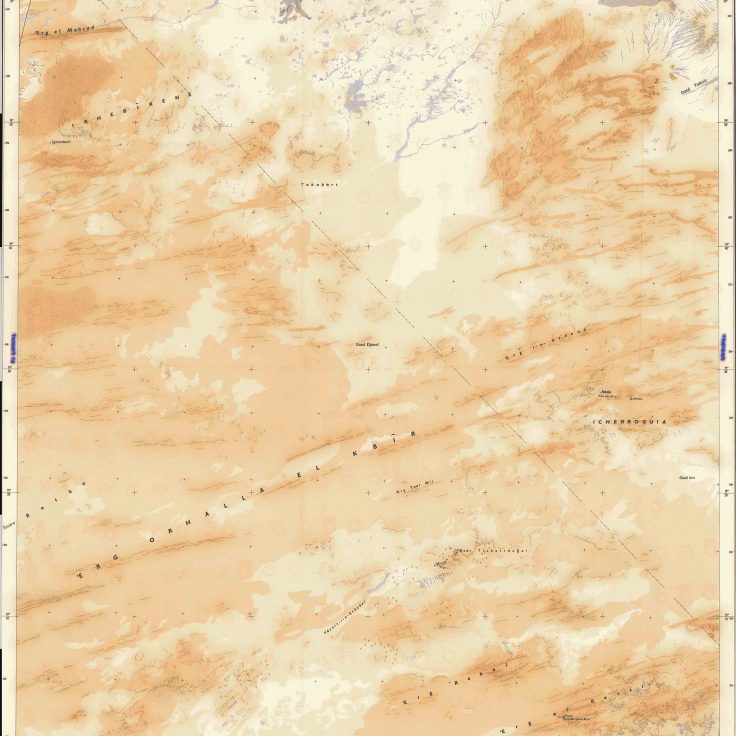

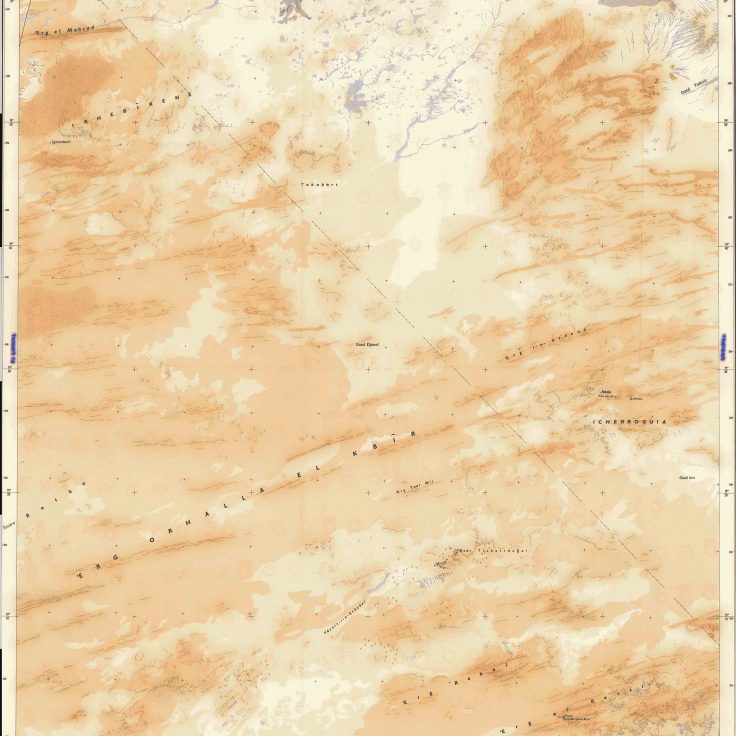

| 37 – El Mamouel. In this central region of the Malian Sahara, the dunes of Erg Orhalla El Kbir are oriented east-west, following the continental trade winds blowing from the NE. Further south of the Tropic of Cancer, the dune chains influenced by the SW monsoon winds are oriented NW-SE. |

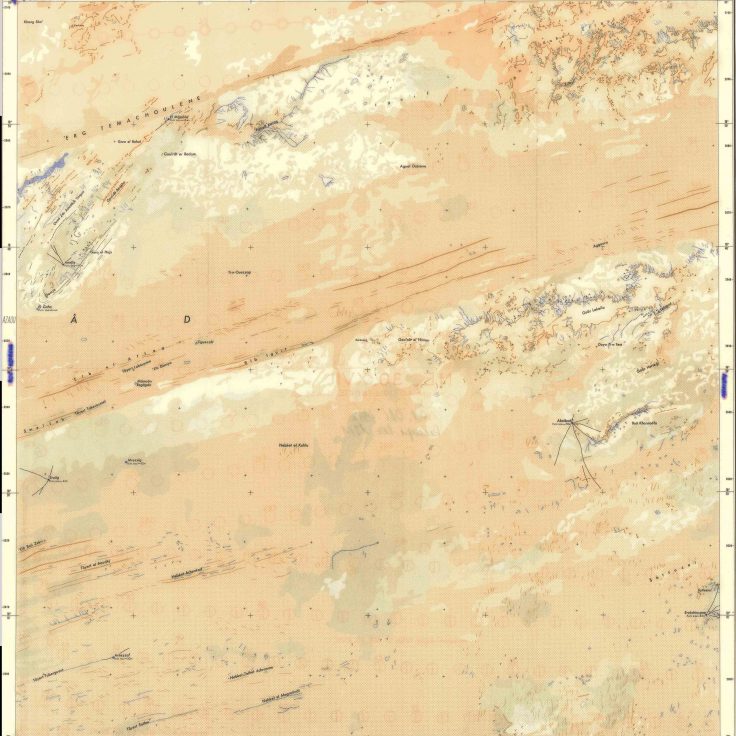

| 38 – Elloul. The different shades of brown used by IGN cartographers to represent the dunes, fixed sands and sandy plains of the Elloul region make it a work of art in its own right. The map shows the eastern extension of the Tanezrouft, a hyper-arid region which extends from Mauritania to the Timetrine massif in northeastern Mali. This region marks the limit of the West African craton, an old and stable part of the continental crust that has survived cycles of merging and rifting of continents for hundreds of millions of years. |

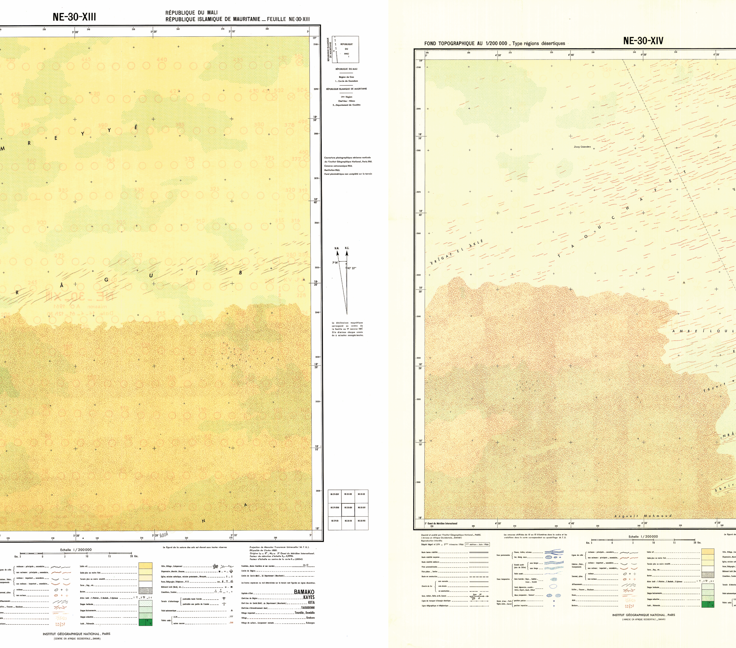

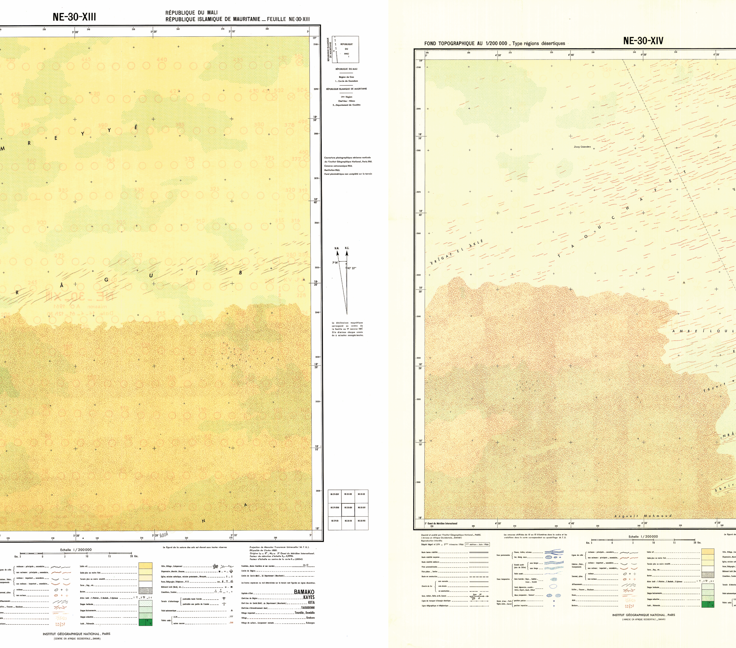

| 44-45 – NE–30–XIII/NE–30–XIV. These maps of western Mali are dominated by Aklé Aouana, a vast expanse of tangled dunes that give the impression of a sea of sand. These aklé arise in regions where sand is abundant and the wind comes from a single direction. The dune network consists of a sinuous ridge running perpendicular to the wind, and made up of crescent-shaped sections |

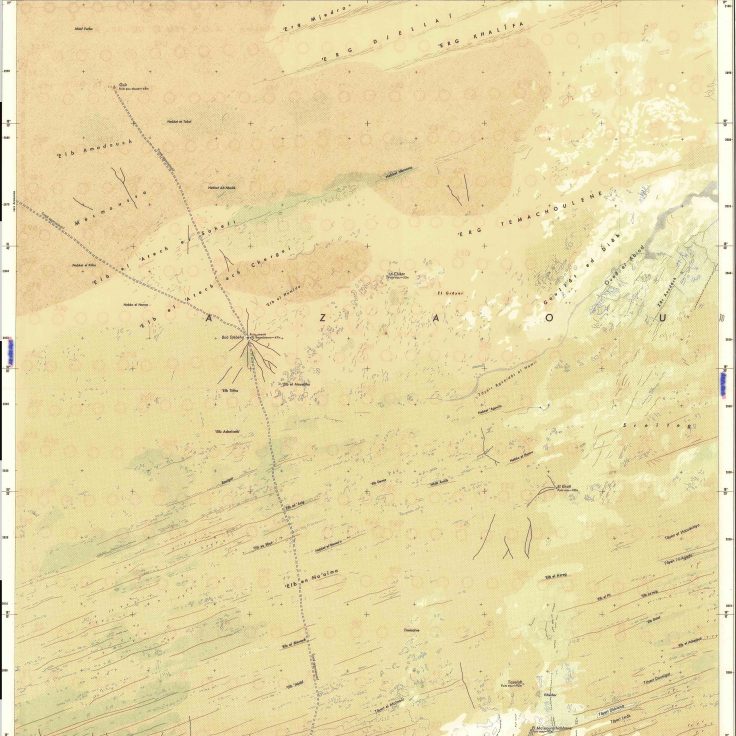

| 46 – Araouane. Araouane marks the boundary between the fossil dunes stretching from the loop of the Niger River to the nineteenth parallel and the living dunes of the northern Sahara. The dunes have an east-west orientation, fanning out slightly to the north. The distance of around 3 km separating the cordons (tayart) is so regular that it is used as a unit of distance by the nomads of the region. |

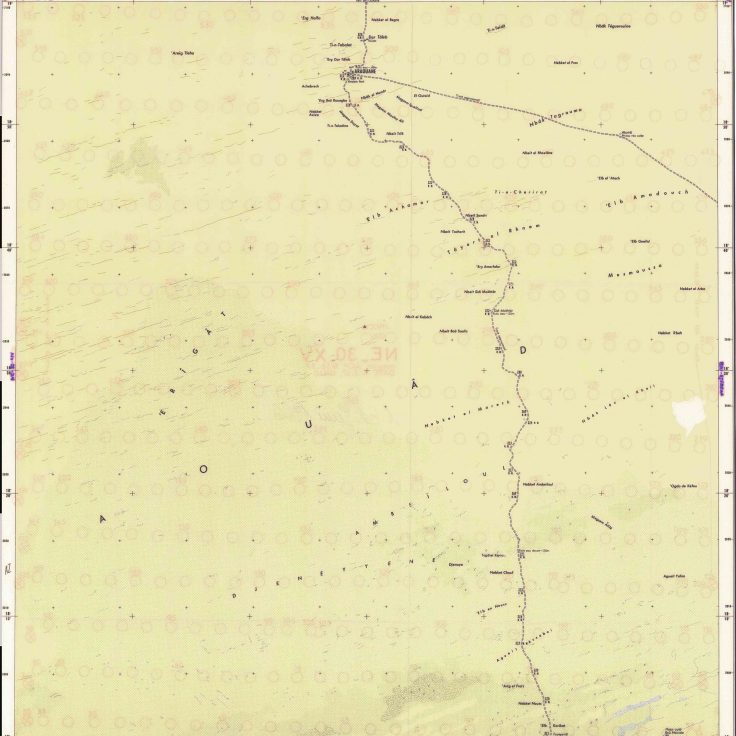

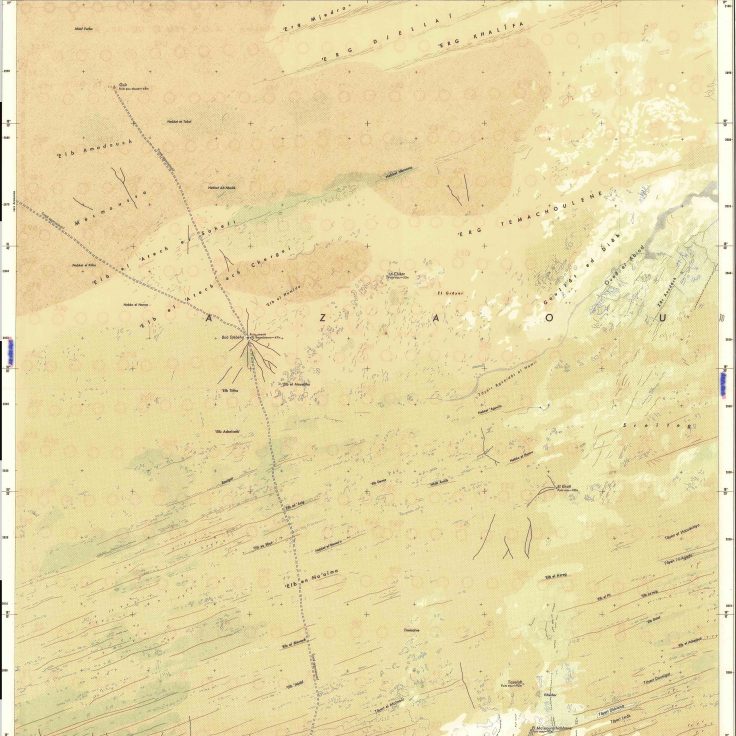

| 47 – Boû Djebeha. Boû Djebeha is a well located SE of Araouane in northern Mali. Despite its remoteness, the little well is a central place: all the tracks converge here. In an arid region like the Sahara, central places do not have to be heavily populated, or inhabited all year round, to provide unique goods and services. In the absence of permanent human settlements, central places emerge at the crossroads of social networks, where and when nomads gather to celebrate the end of the rainy season, traffickers meet to smuggle migrants, or radical extremist stop to buy supplies. |

| 48 – Abelbod. In the Azawad region north of Timbuktu, water is buried deep beneath the ground: more than 40 m in Anefis, El Mâmoûn, Eroûg and Mrezzig, 78 m in Abelbod, and 84 m in Erakchiouene. These deep wells were dug by professionals hired by the region’s tribes. Known as ighuras in Tamashek, they can be up to 100 m deep and need regular maintenance to prevent silting. The wells in this region were already indicated on the topographic maps produced in the early years of colonization, testifying to their historical importance in camel traffic between the towns of the Niger River Bend and the Timetrine massif. |

| 55 – Zouîna. This border region with Mauritania is almost entirely covered by crescent-shaped dunes called aklé. The Zouîna well, over 60 m deep and located in Mauritanian territory, is the only permanent water source and the end of the rough track that leads to Bassikounou, over 135 km further south. |

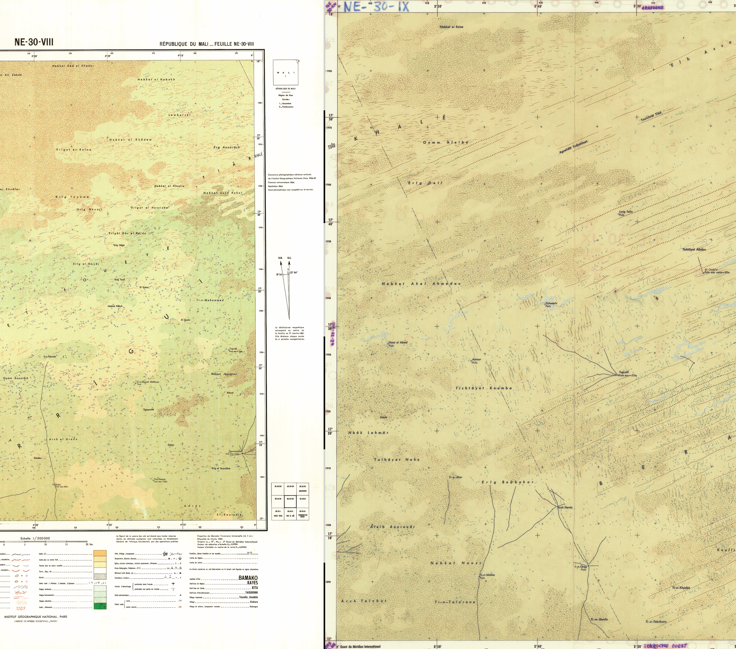

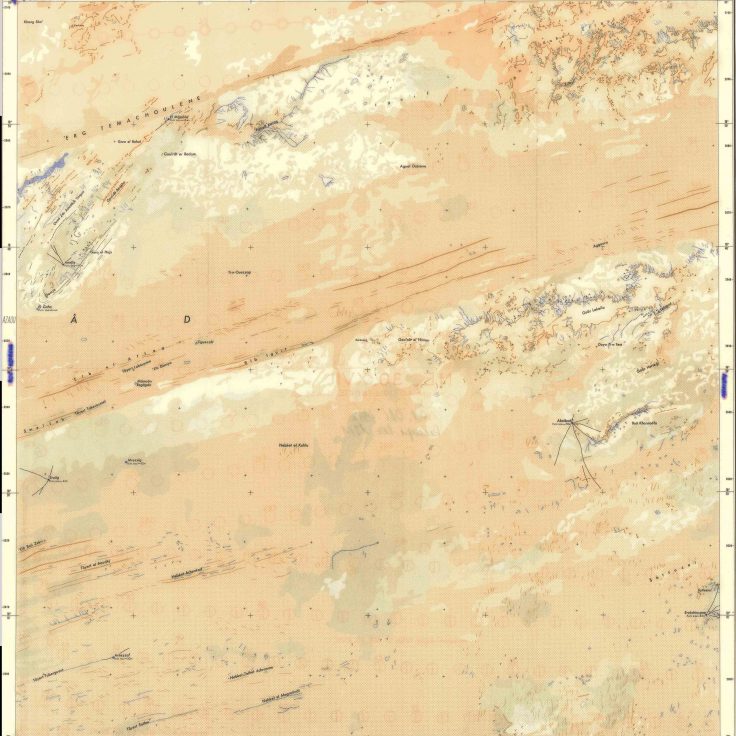

| 56-57 – NE–30–VIII/NE–30–IX. Saharan ergs are often grazing areas, as here in the Irrigui region northwest of Timbuktu. Five large wells more than 50 m deep are used to water animals and service nomadic camps. Over time, each well has become the hub of a network of tracks that radiate out in all directions. |

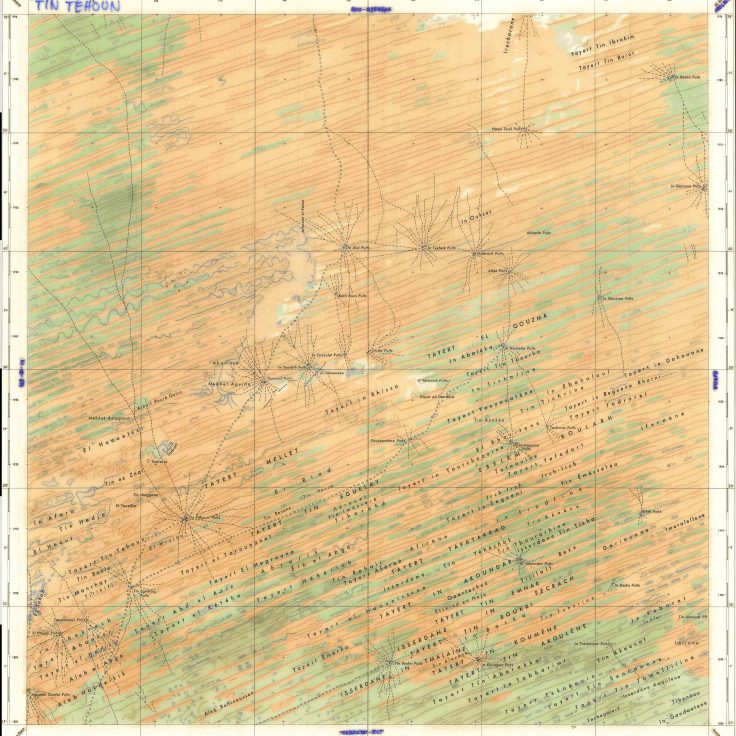

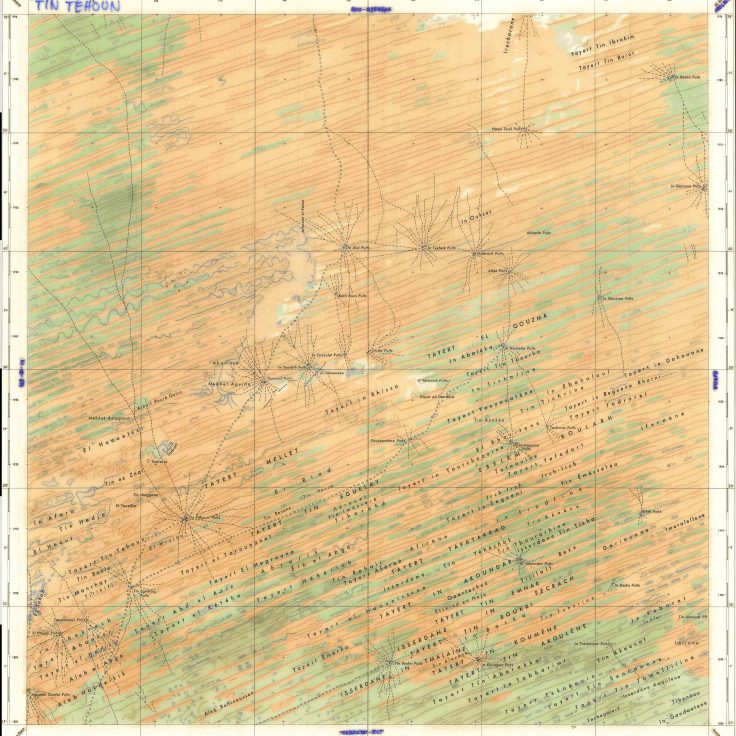

| 58 – Tin Téhoun. In the Azawad region north of Timbuktu, all tracks converge on the wells. The region is crisscrossed by fossil dunes stretching over 200 km from SW to NE. This ancient erg formed during the last glacial maximum (24,000-15,000 BP) is still clearly visible under today’s Sahelian vegetation. Azawad is a vast pastoral area encompassing northern Mali and northwestern Niger. |

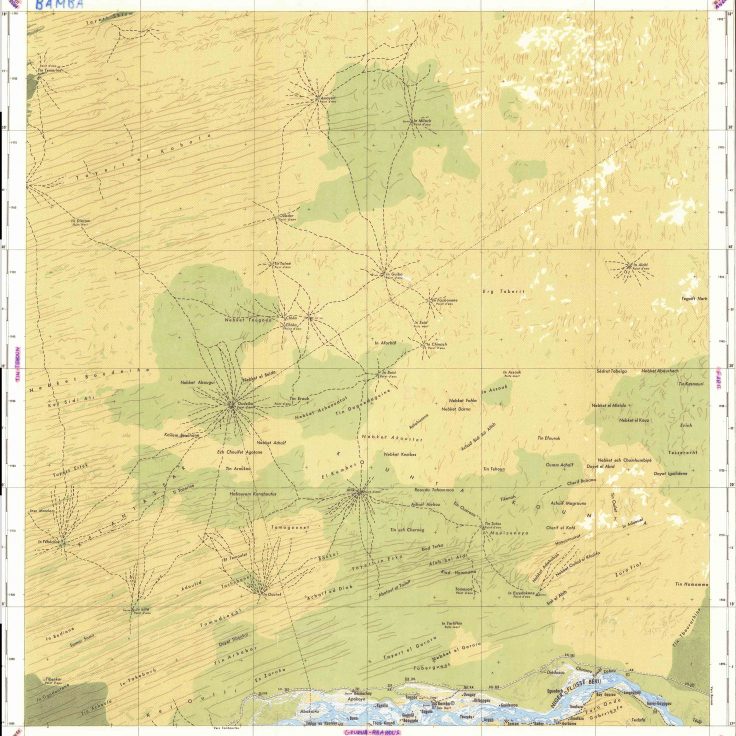

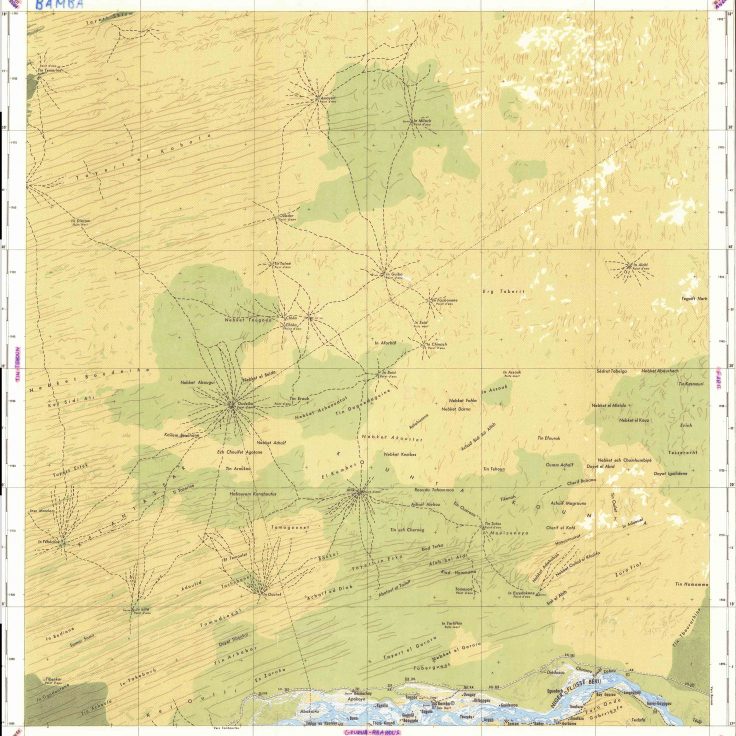

| 59 – Bamba. This spectacular map of the Bamba region shows the River Niger before it begins its southward descent. The northern part of the Niger Bend is a vast area of grazing land located on long sand dunes. IGN cartographers have patiently reconstructed the tracks used by herders to the region’s wells. Some of these wells have dried up (puits morts in French). This region is the territory of the Kounta, an Arabic tribe who plays a major commercial and religious role in northern Mali. The Kunta have long controlled the major trans-Saharan routes linking Mali to Algeria. The Malian civil war has brought back old divisions between the Kunta and their traditional vassals, the Tilemsi-Lamhar, who live further east. |